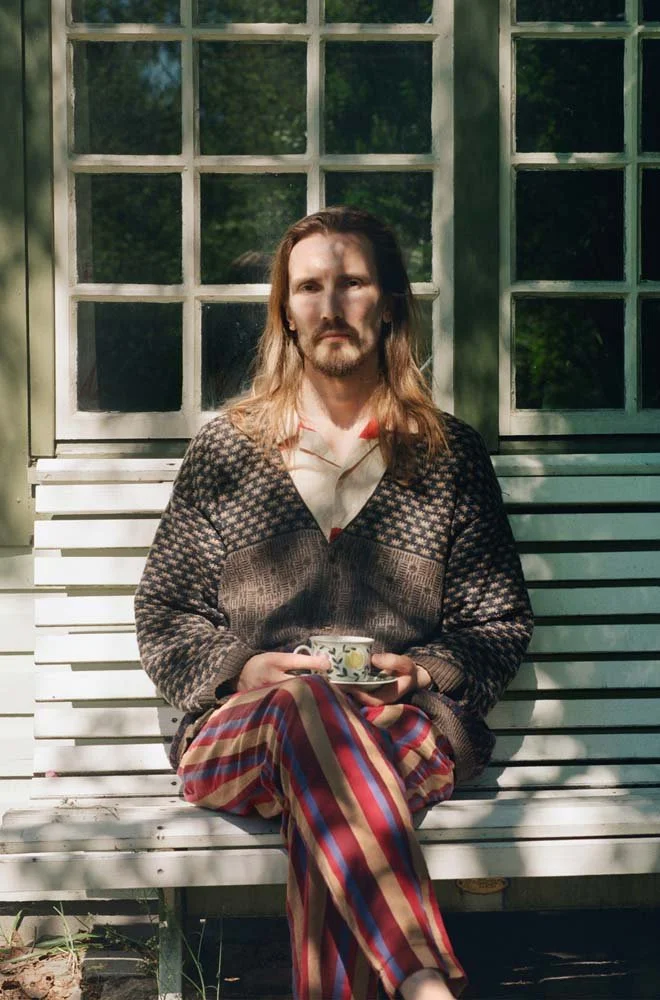

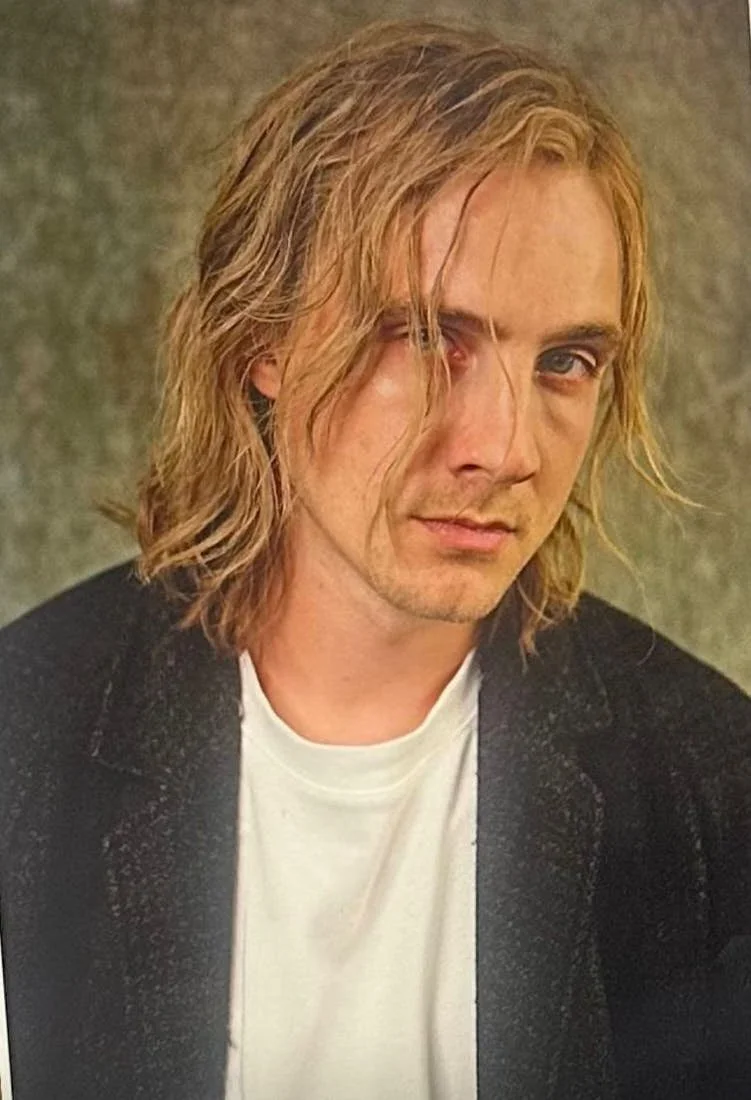

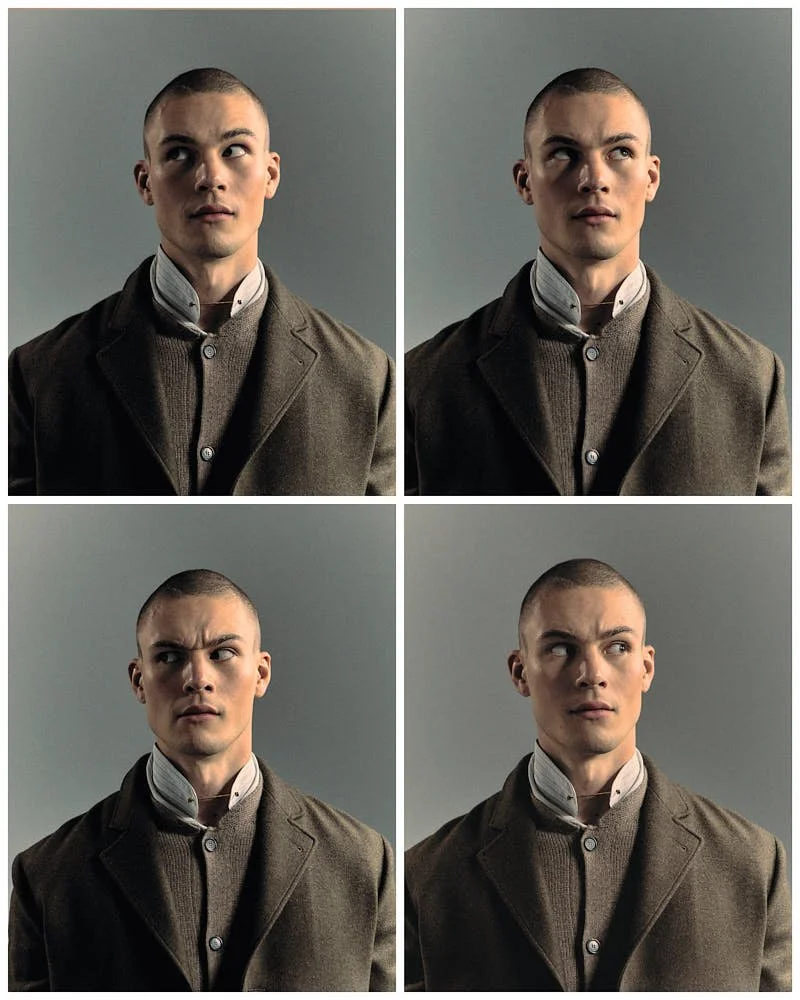

That’s Bill Kaulitz

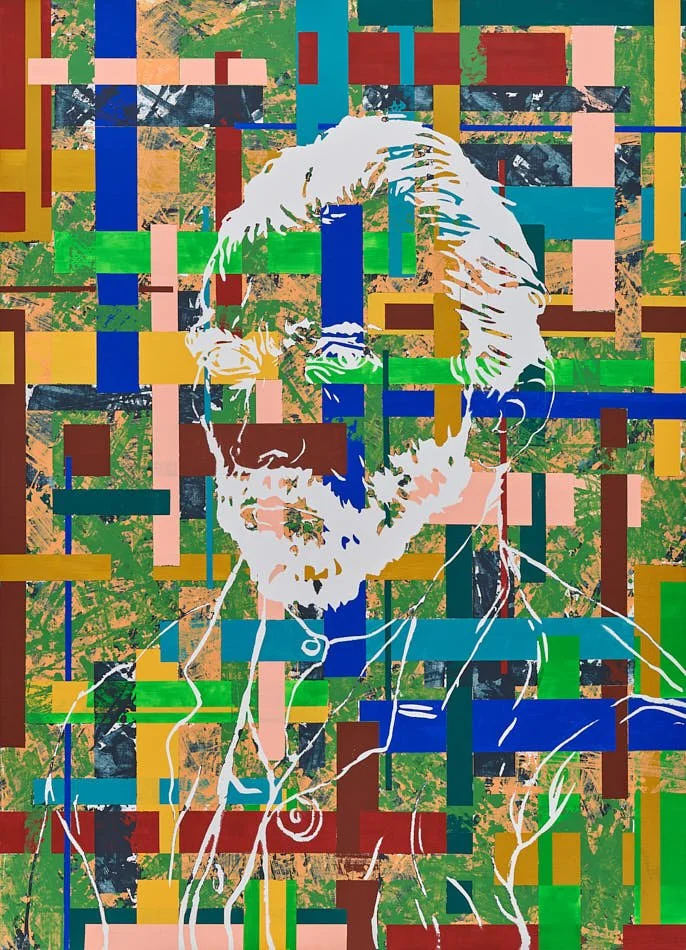

Offline, Unfiltered, and Entirely Present

The Algorithm Has Left the Chat—Bill, a Pink Swimsuit, and the Real Headline

interview + written ALBAN E. SMAJLI

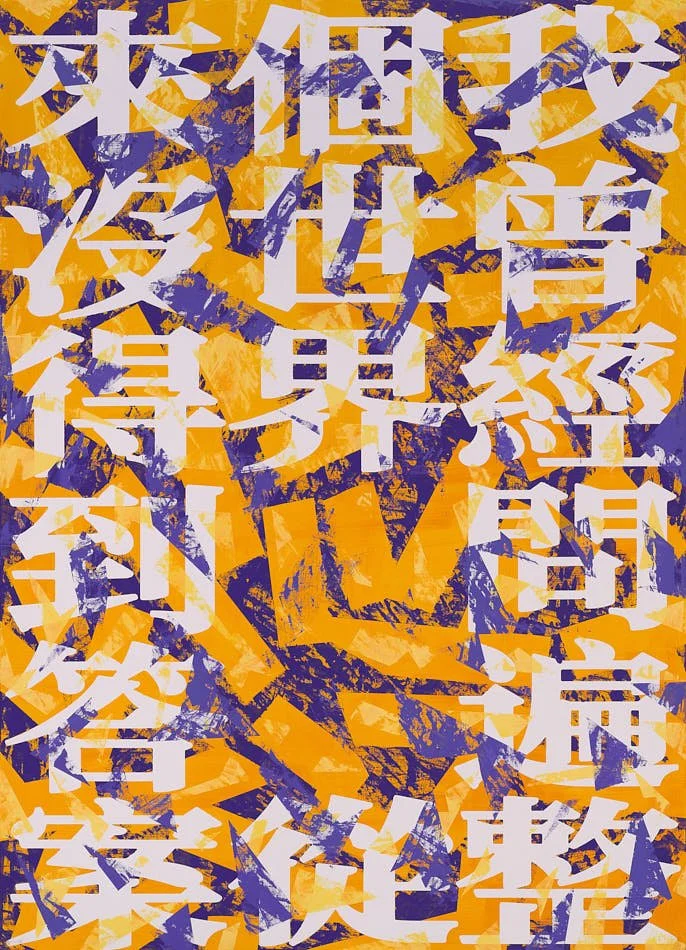

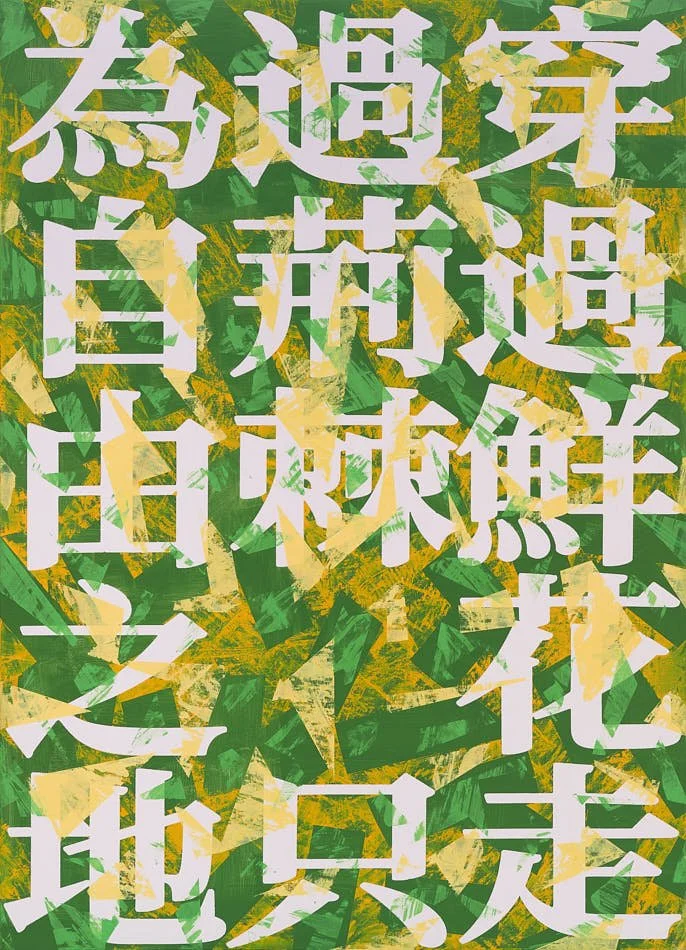

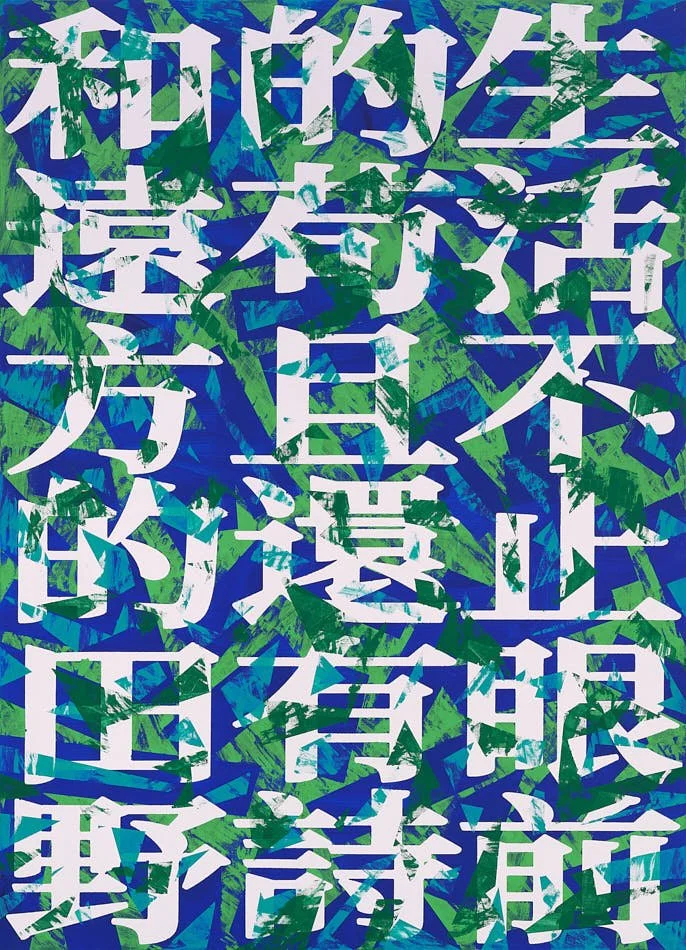

Something about Bill Kaulitz disrupts all expectations about fame, he moves with a kind of impulsive certainty, always spinning a little outside the expected choreography. Once the ringleader of a hair-gel-fuelled teen frenzy, he now fills his days with dogs, spontaneous notes, late-night Instagram DMs, the second season of Kaulitz & Kaulitz playing out on Netflix, and the kind of wardrobe decisions that started early—long before anyone was watching, when he swapped trunks for a friend’s pink swimsuit on a crowded beach, discovering the addictive thrill of attention before he had words for performance.

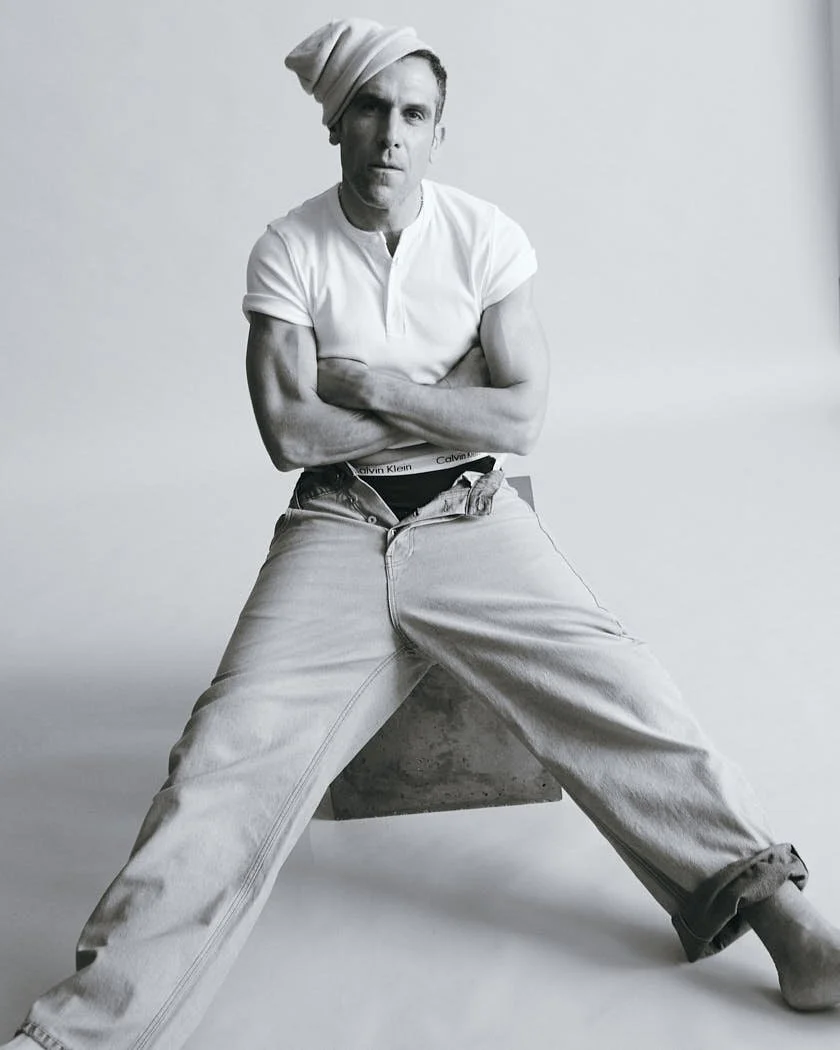

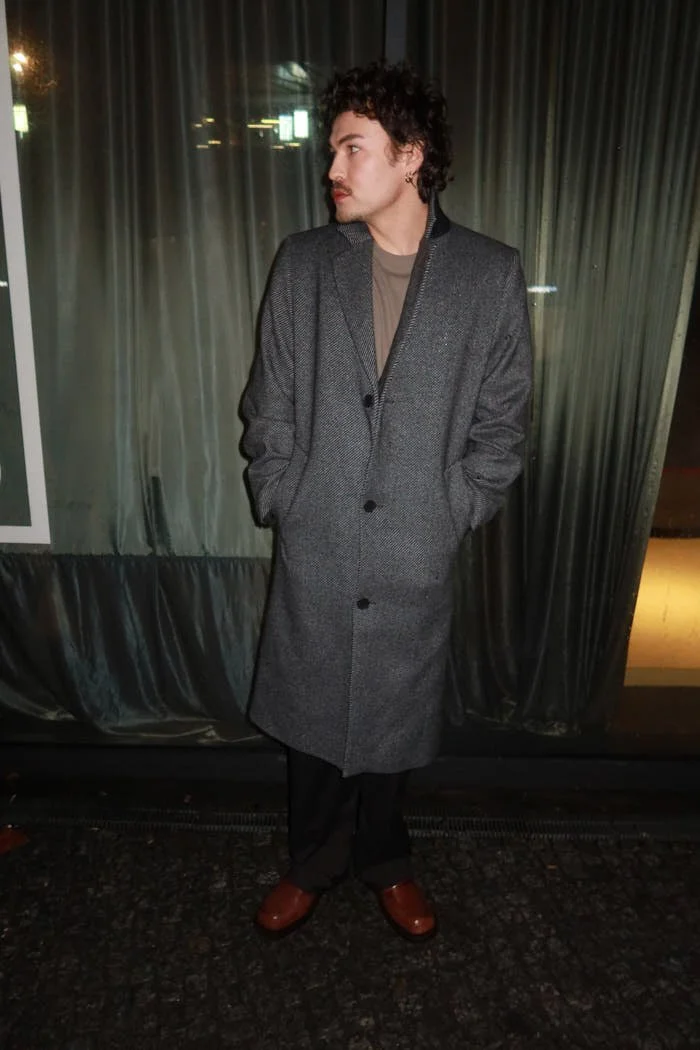

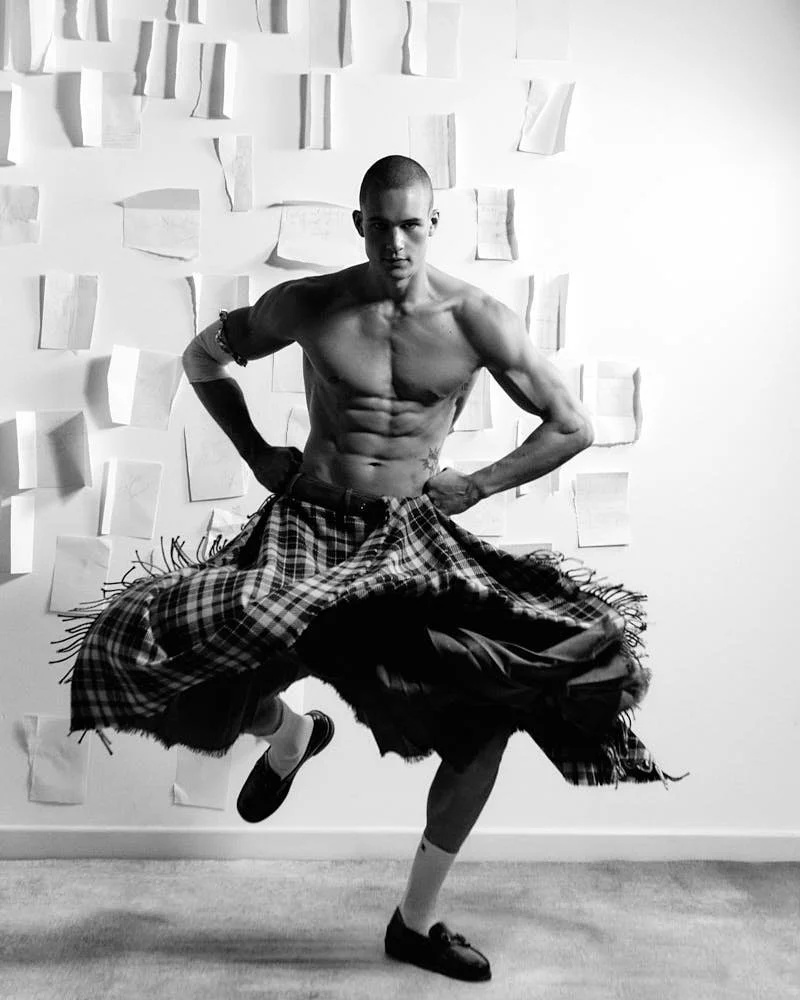

Bill wears total look by VERSACE

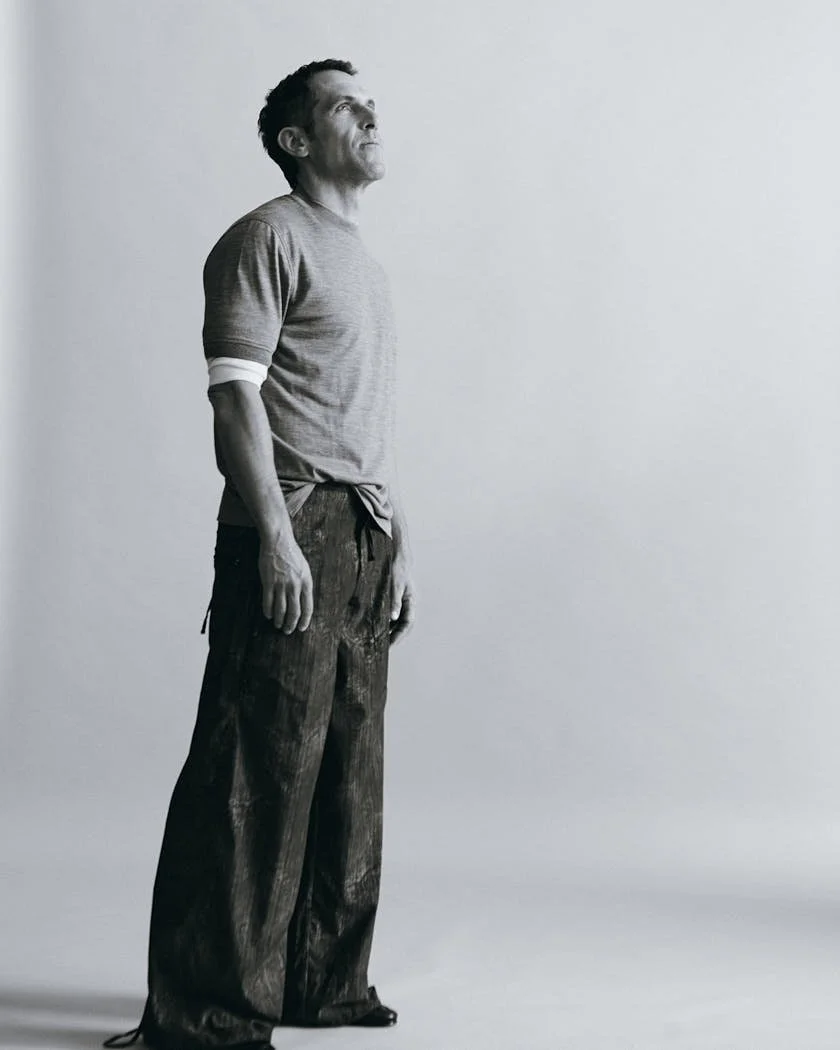

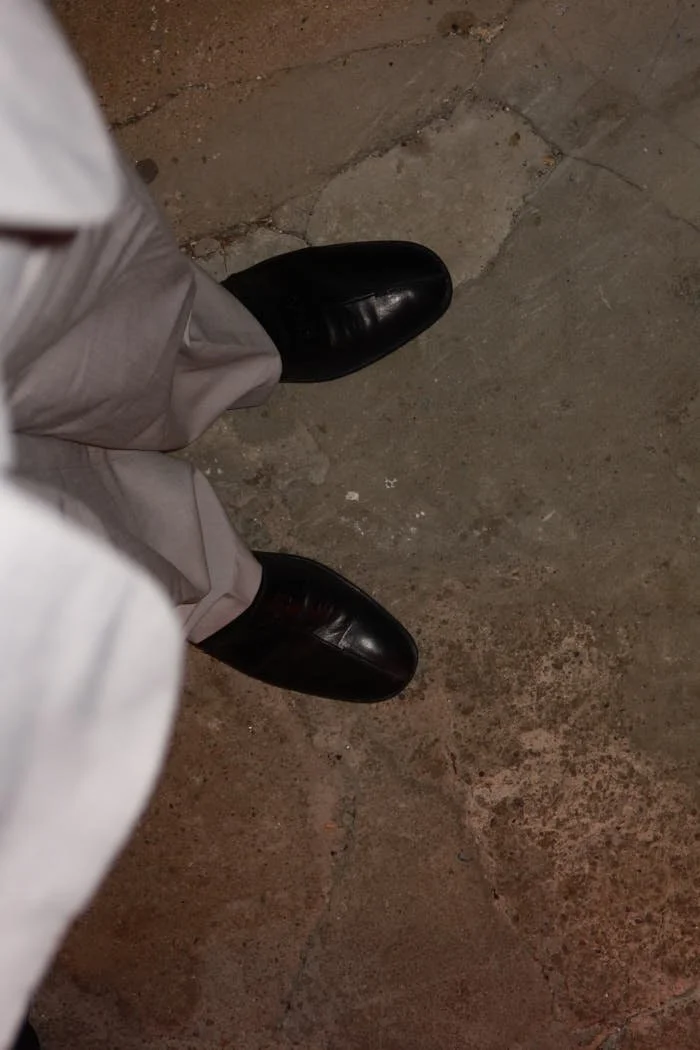

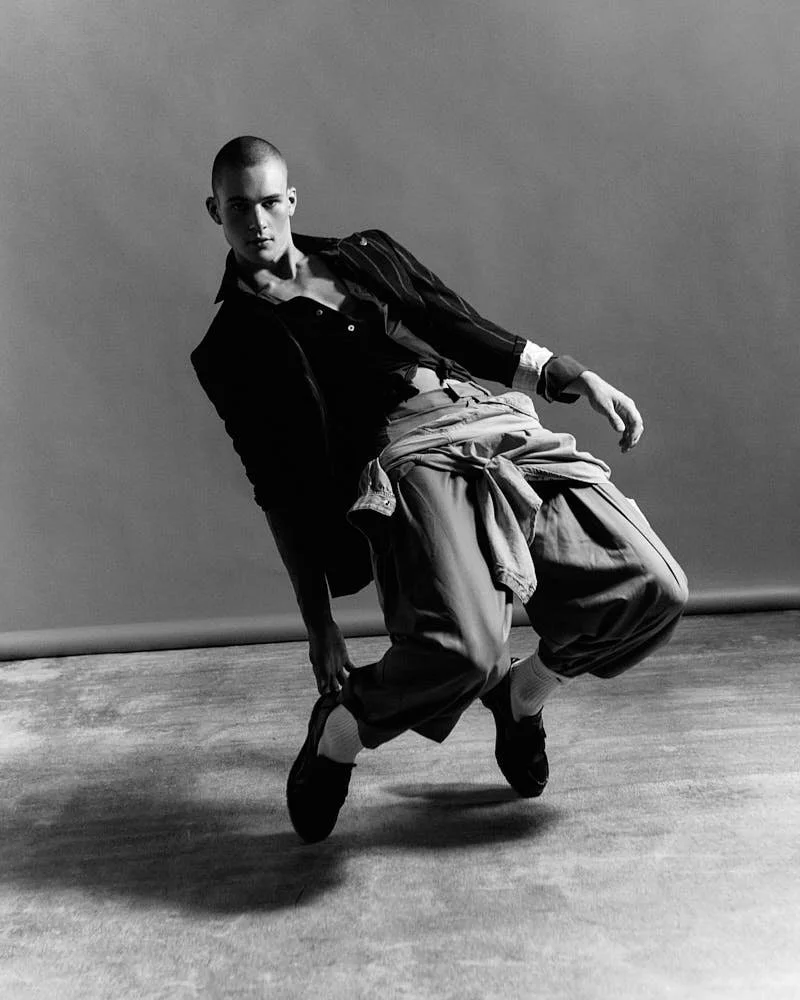

Bill wears a total look by VERSACE and shoes by SCAROSSO

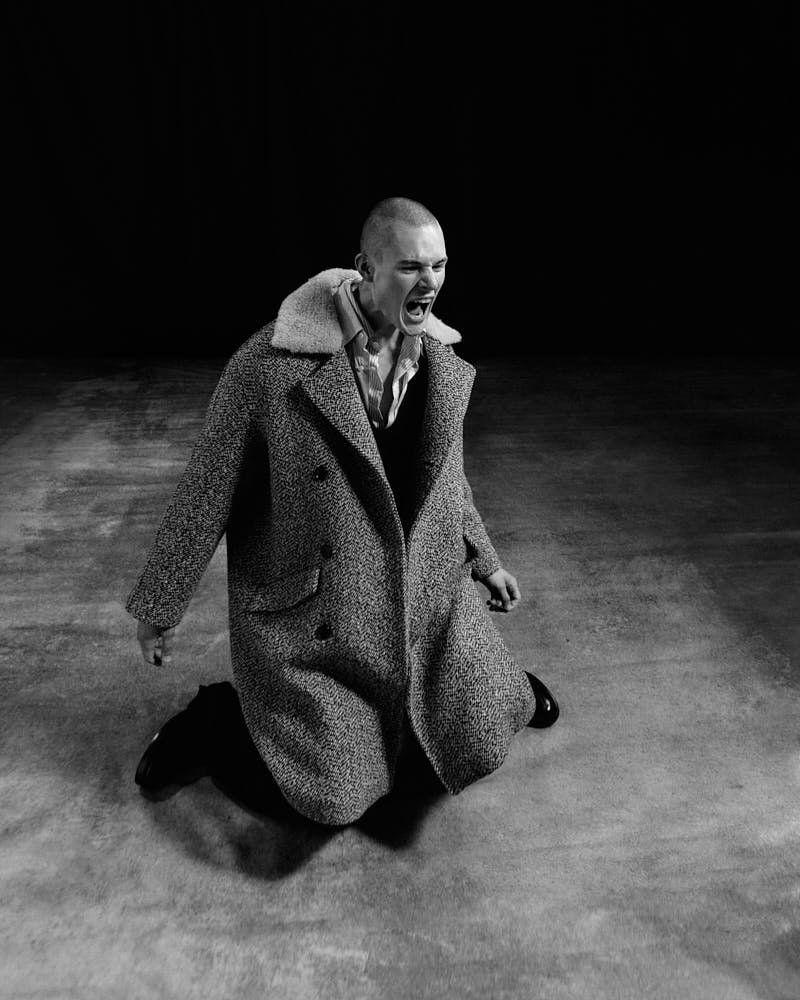

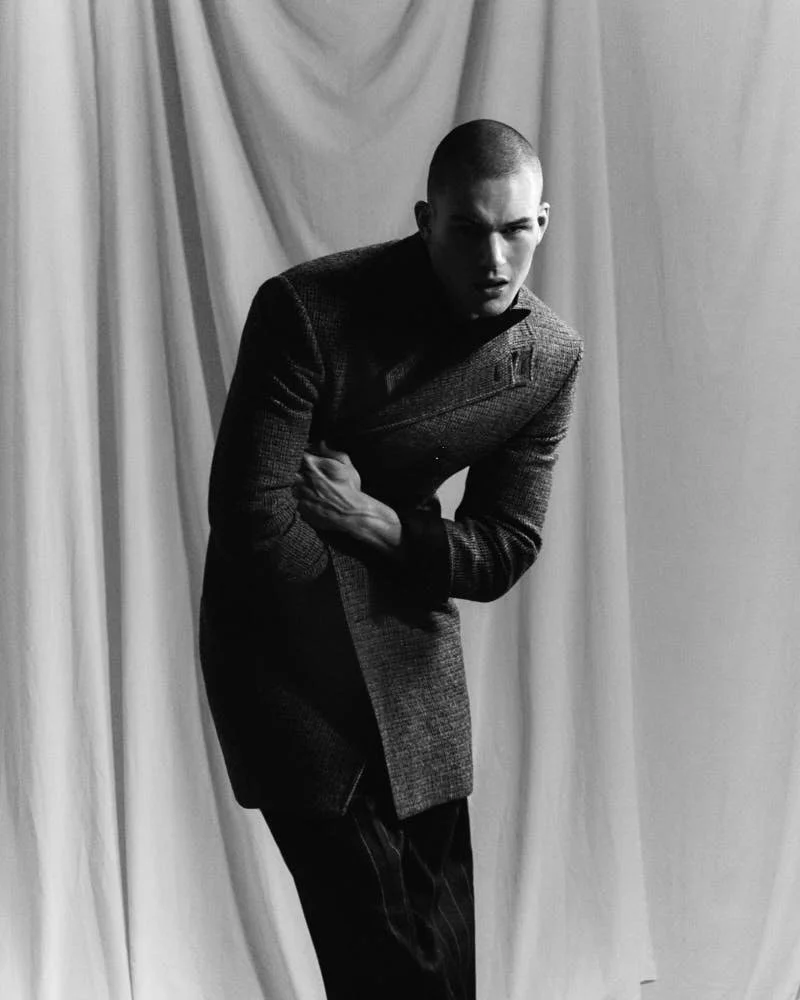

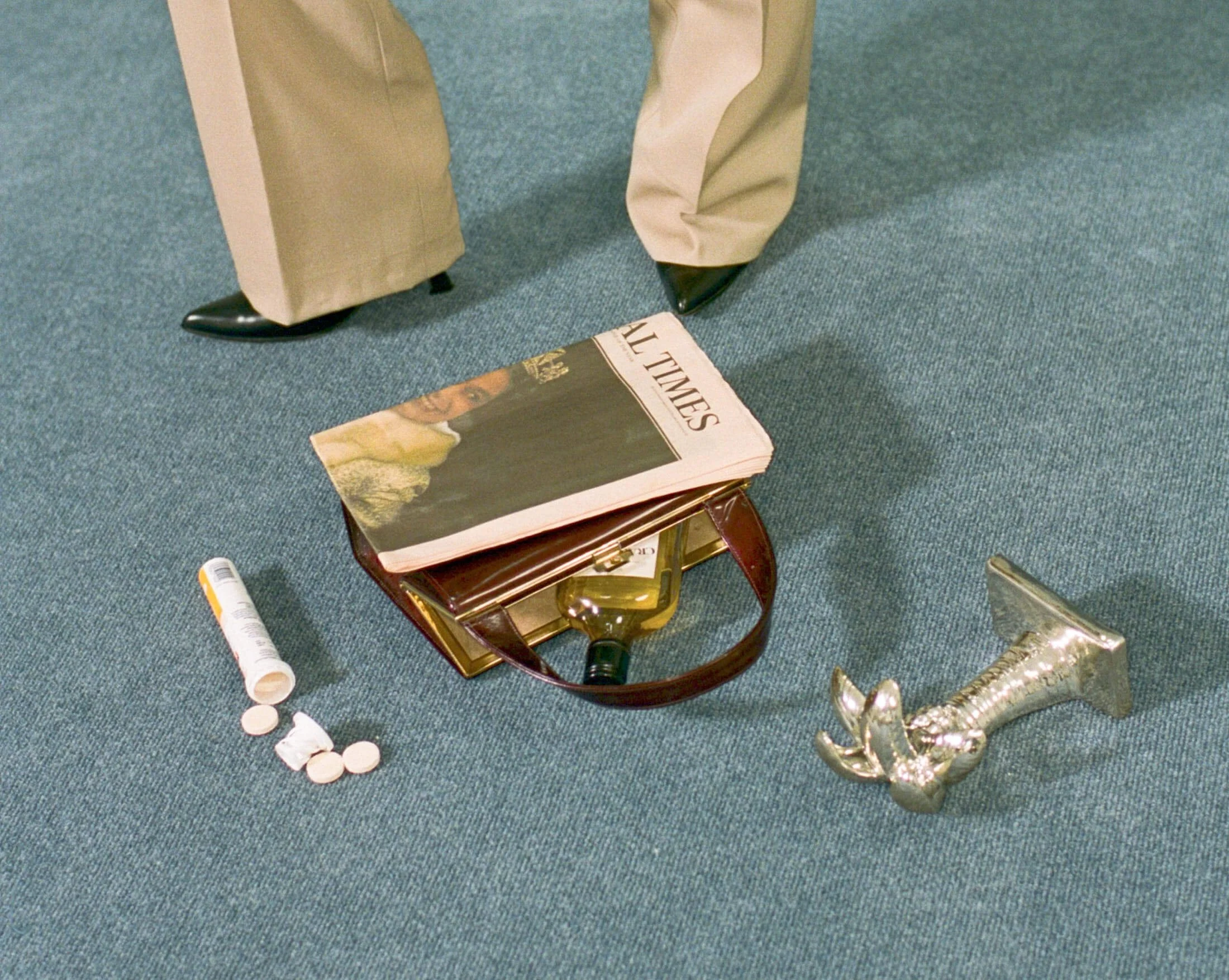

If his closet could talk, it would offer up a mess of confessions about last-minute fashion choices, impulsive adventures, and those secret, tangled stories that happen only after the city has gone to sleep—always accomplice, each garment a collaborator in Bill’s ongoing refusal to blend in or apologize. Recklessness and vulnerability orbit together here, just as Bill embraces every emotion fully—choosing to feel loneliness, joy, and even loss in their sharpest forms, collecting experiences the way some people collect shoes.

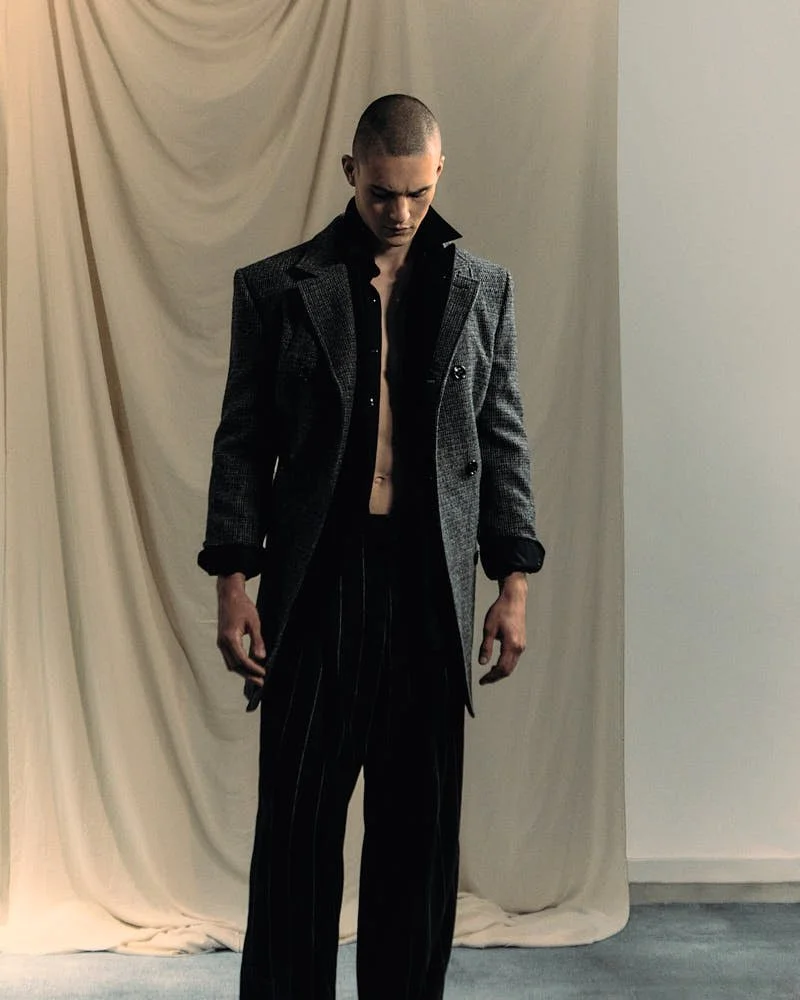

Remove the endless scroll, mute the digital noise, and Bill remains someone searching for real connection, content to swap the feed for the company of friends, the calm of jazz, the comfort of champagne, and the gentle presence of his French bulldog, Alfia. There’s always another scribbled note or whispered Maus for the people who matter, secrets layered beneath eyeliner and tucked into diaries, never needing an audience, only the satisfaction of having lived every minute wide open. Bill drags his own weather with him, shrugs off nostalgia the way most people dodge last season’s trends, refuses to archive any version of himself unless it’s handwritten and hidden somewhere even the algorithm can’t reach. He exists in a loop of invention and desire, never looking back, never asking permission, just rerouting the atmosphere every time he walks into the room. Never watered down, never apologizing, so entirely present you half-suspect the world’s only just now learning to keep pace.

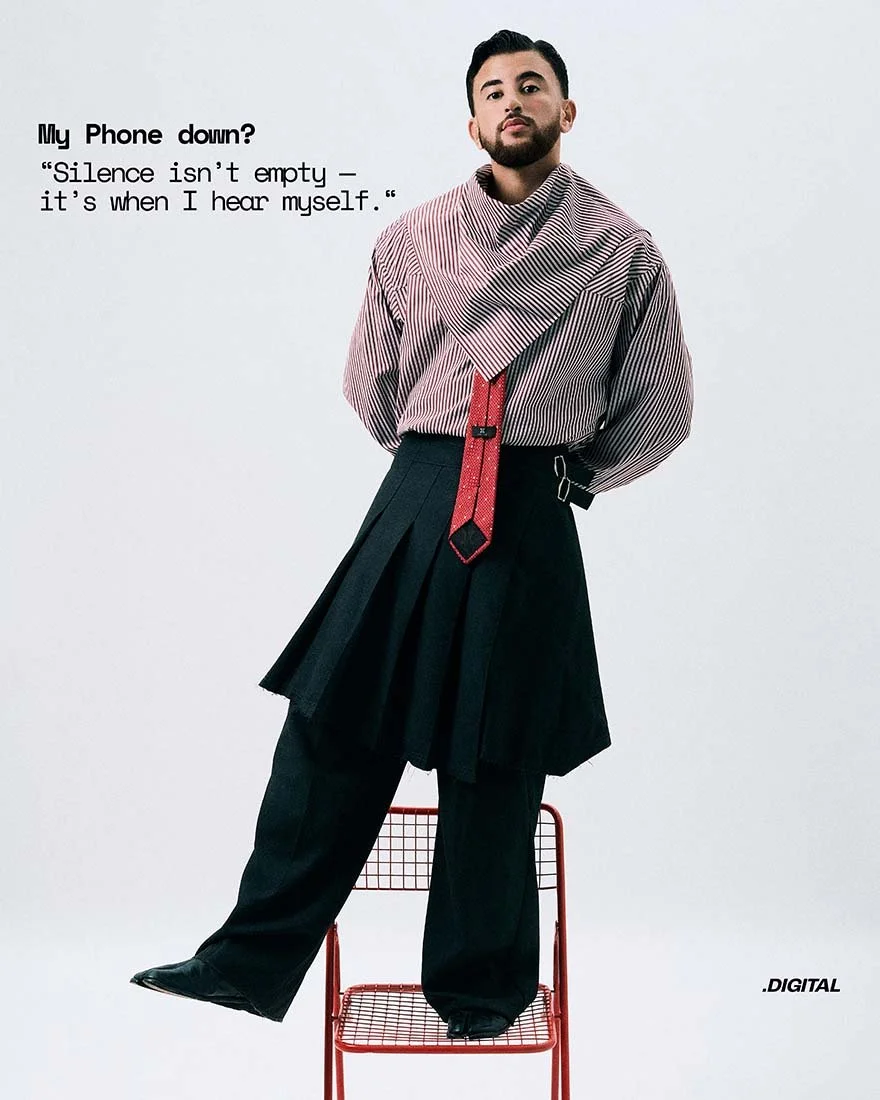

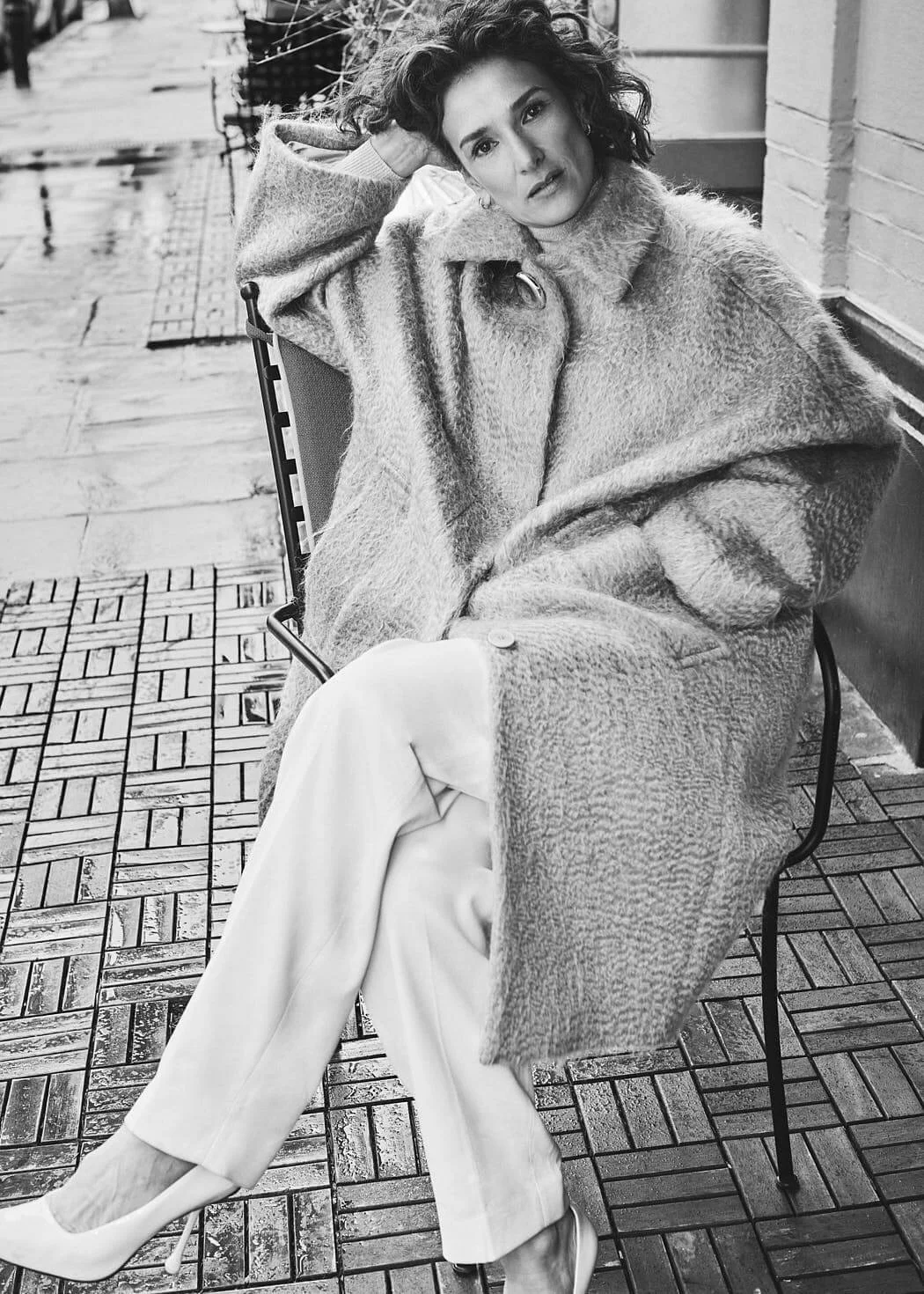

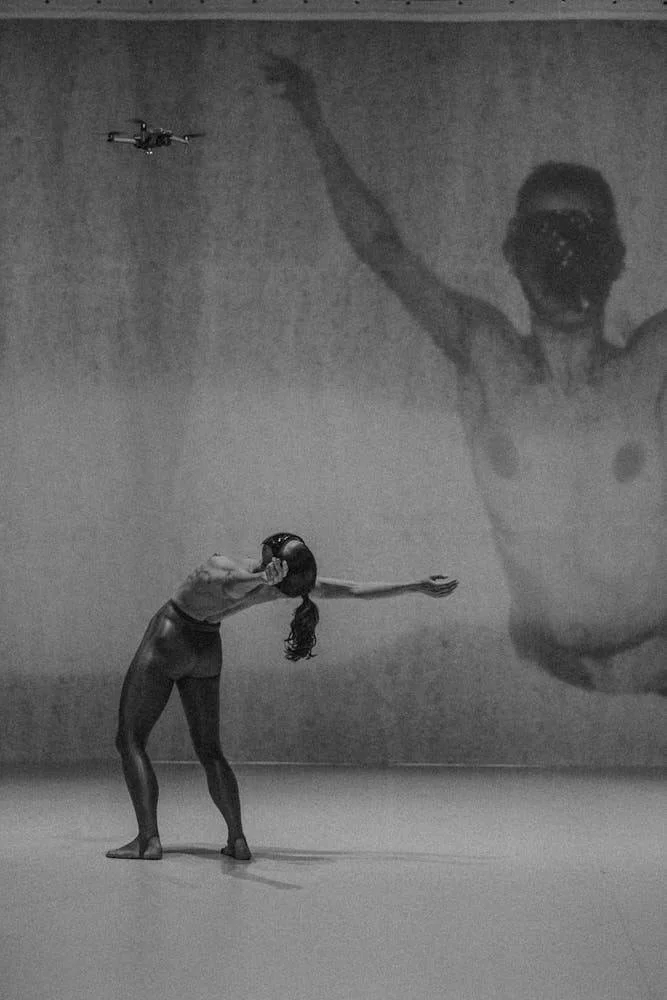

Bill wears a sweater and bag by HERMÈS, belts, gloves, and trousers by 032C, and shoes by SCAROSSO

Alban E. Smajli

If you had to live in a world without mirrors or cameras, how would you define your identity?

Bill Kaulitz

Just through instinct I guess! I've always trusted my instinct. Laughter too! I'm generally a very positive person. My biggest traits are being quirky, spontaneous and ambitious, I’d say.

Do you remember the very first time a mirror winked back at you and said, “Yes, babe, this is it”? What were you wearing?

OMG. That could have been very early on. When I was about 5 years old and my mom took us to the beach, I decided to wear the pink swimsuit of my friend Katharina, instead of my boring trunks that every boy wears. So we swopped. I felt super alive and loved the attention from all the people starring at me. I always loved to stand out and break rules. I guess that started at a very young age.

If your closet could speak like a moody ex, what secrets would it spill about you?

That I don't doubt my fashion choices a lot, even if I maybe should. I don't think too much. I'm super fast and trust my gut when it comes to clothes. I'm really not a diva, even if sometimes i'd wanna be. It would probably also say that I've been in here with more than just one guy having sexy fun. When you're out of the closet it can be pretty fun to go back in ...hahaha.

How do you actually handle loneliness? The kind that doesn’t get filtered through reels or drowned in airport noise?

I don't! I give in to the feeling! I love to feel all the feels and loneliness can also make you feel alive. I think the worst feeling you can have, is to feel nothingness or jaded or numb. As long as you feel loneliness every once in a while, you know you are living and still have a fire burn inside you that has longing and a craving for connection and people. I gotta admit I'm doing pretty good on my own. I hardly ever feel lonely but I think that's because I have an identical twin. I even go on vacation alone all by myself. It's the best.

Bill wears a sweater by 032C, a jacket and trousers by HERMÈS, and shoes by MARSÉLL

Bill wears a shirt by ARKET and a coat by JOSEPH

What do you think you would miss the most if there were no social media or mobile networks today?

The inspiration that comes from it. I'm a very visual person so I love photography, architecture, fashion and the access to all of it with just a fingertip. Also I would miss my number one flirting and dating tool. Haha. Cause I date mostely through Instagram.

If you could ghost one memory forever, digitally and emotionally, what would you delete?

The death of my two doggies. That was very hard on me. I'm an animal lover and my dogs were like my kids. The way they both passed was very sudden, way too early and unexpected. That's a memory that I'd like to forget. But I'm not one who lives with regrets, so I can't really think of anything else I'd like to forget.

How would you go about dating if you had to do it completely offline today?

I would probably party even more than I do now. I love to go out and meet new people through mutual friends or just strangers at a rave. I love to have a good drink at a bar and make friends. Thats the best! I also love house parties, birthdays and my favorite are weddings. I always end up with someone at a wedding.

Bill, imagine being offline without any technology or social media, how do you cope with just being alone with yourself?

Could I still watch TV?

Of course, TV is still offline

I love movies and old TV shows. Thats like therapy for me and calms me a lot. If I wouldn’t have a TV either I would probably lay out by the pool with a good bottle of champagne, listen to jazz music and play with my doggie Alfia. I adopted her a year and a half ago. Shes a little merle frenchie and my absolute everything.

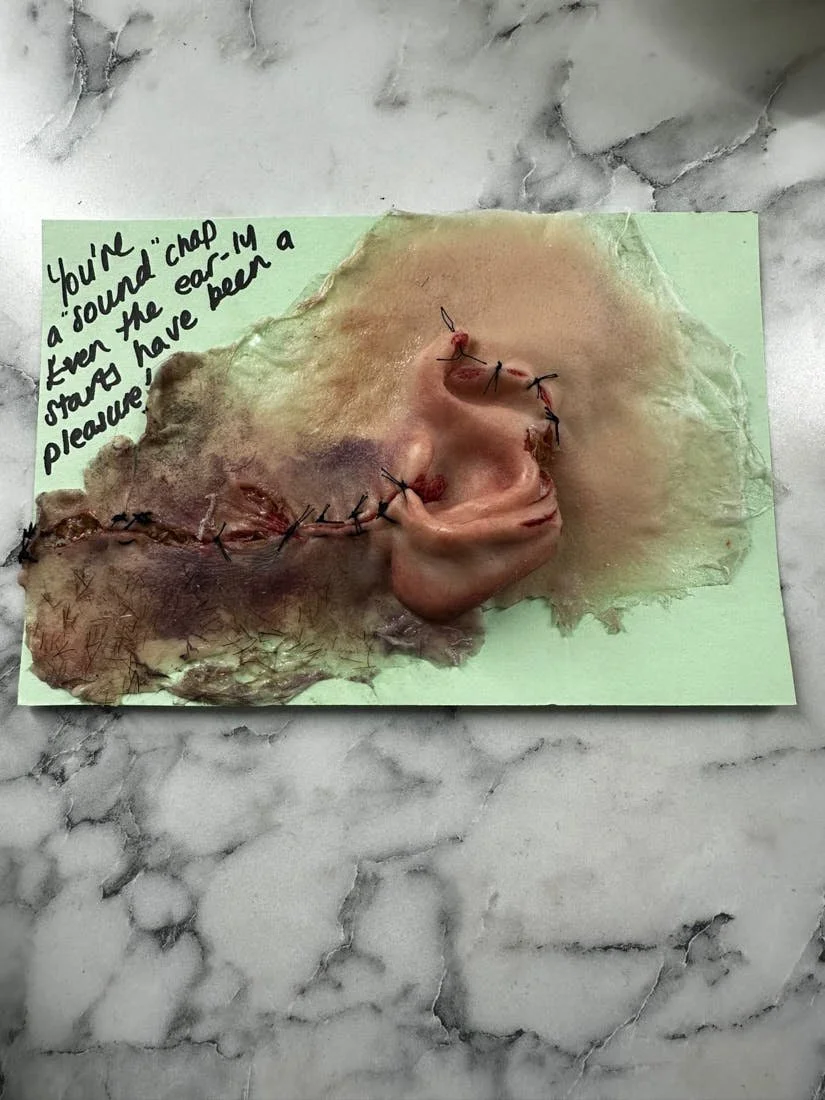

When was the last time you wrote something with your actual hand? Like pen, paper, no autocorrect?

Not that long ago. I wrote a love letter to fashion for a big magazine very recently. I love writing by hand. I do it every day. I have a little scribble book where I write in every day. Just notes and stuff I can't forget. Also all the notes for my weekly podcast are always handwritten and I keep all of them..

Let’s imagine you had kept a diary in 2006, what do you think would surprise people most if they read a page from it today?

That I was hiding a lot of secrets and pain behind those perfectly smokey eyes.

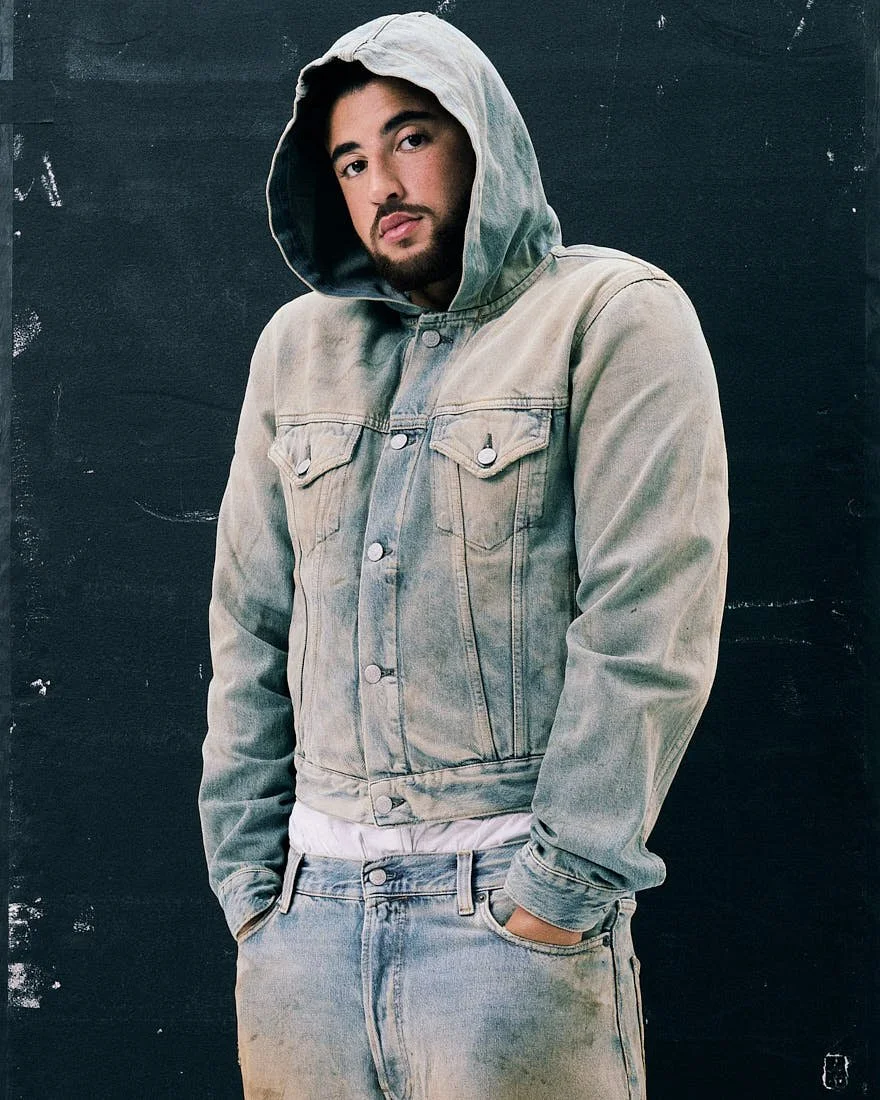

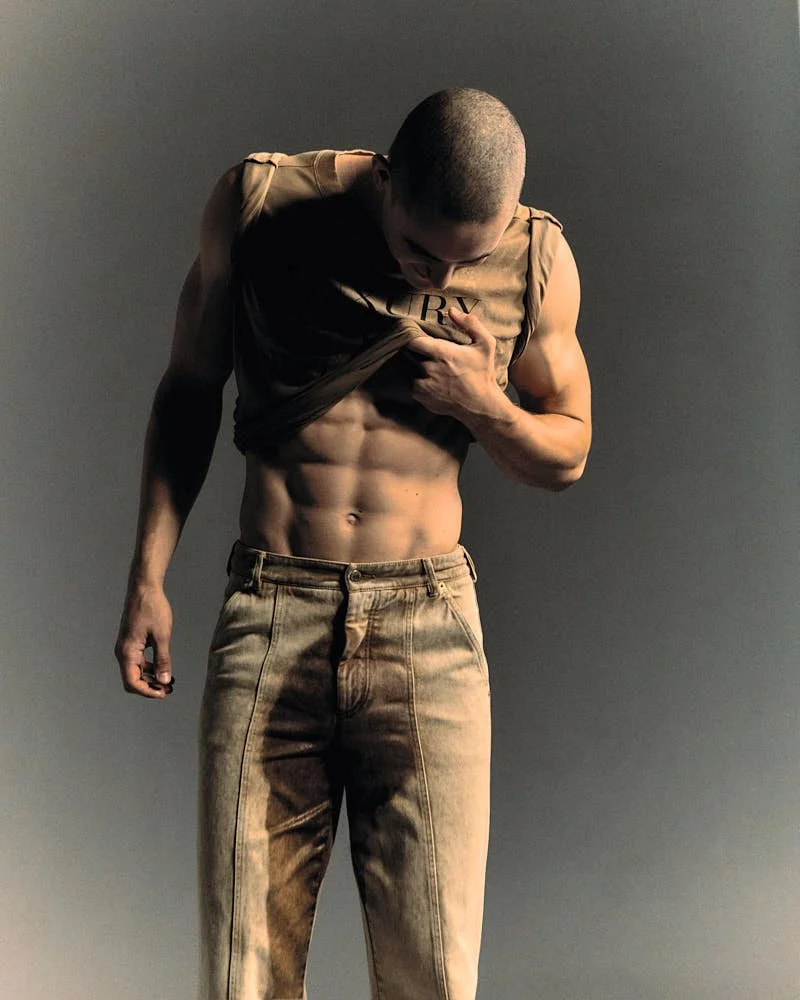

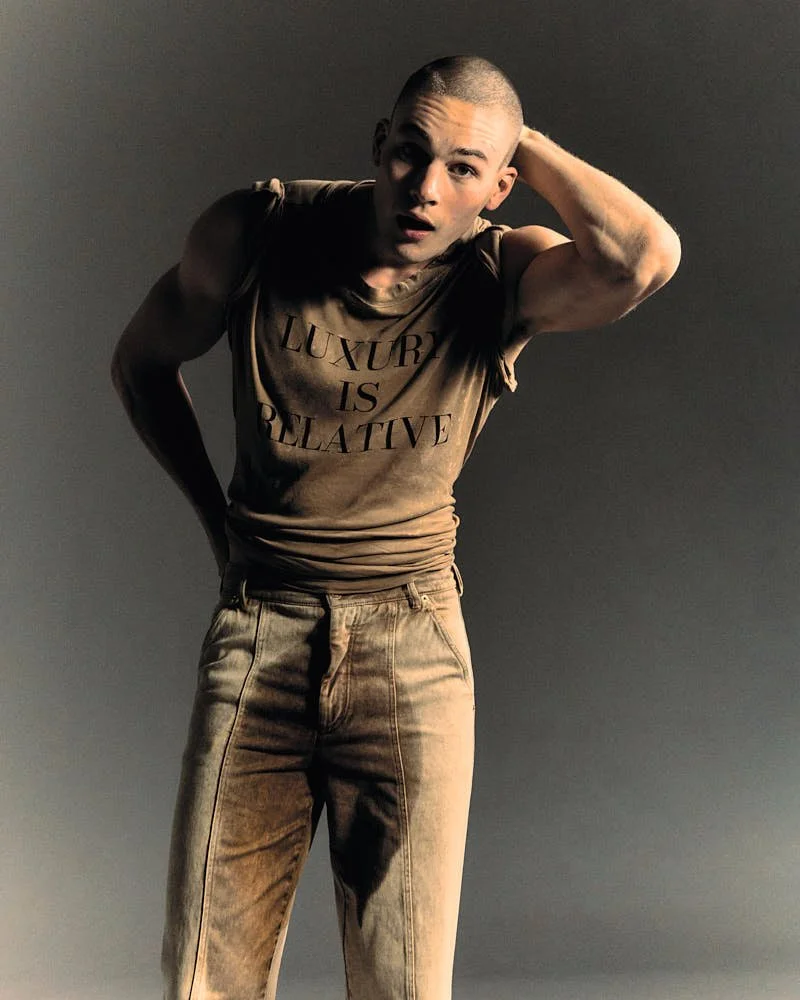

Bill wears a total look by LEVI’S, a brooch by JW ANDERSON, a bracelet by HERMÈS, and shoes by MARSÉLL

stylist ARKADIUSZ SWIETON

hair & make up artist PATRICK GORRA

set stylist NICI THEUERKAUF

photography assistant MORITZ HILKER

styling assistant LEA ISABELL UHLE

copyright LE MILE Magazine / Christopher Puttins for LE MILE Issue 39 "OFFLINE", FW2025/26 Edition

![Unknown [Gloria in Susanna and Marie’s New York City apartment] 1960s Chromogenic print 3 1/2 x 3 9/16 in. (8.9 x 9 cm) Art Gallery of Ontario, Purchase, with funds generously donated by Martha LA McCain, 2015 Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/c5552ea0-419f-42de-95d0-e72f76da9816/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Gloria+in+Susanna+and+Maries+New+York+City+apartment_AGO.121804-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Susanna standing by the mirror in her New York City apartment] 1960 – 1963 Color vintage print 9 1/16 x 7 1/5 in. (23 x 19 cm.) Collection of Cindy Sherman Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/158c7a10-a813-4aa0-a02b-d184a06c982b/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Susanna+standing+by+the+mirror+in+her+New+York+City+apartment_EXH.169577-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Lili on the diving board, Casa Susanna, Hunter, NY] September 1966 Chromogenic print 5 1/16 x 3 9/16 in. (12.8 x 9 cm) Art Gallery of Ontario, Purchase, with funds generously donated by Martha LA McCain, 2015 Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/a1477c4a-2457-4789-a42c-d451bef2c0ee/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Lili+on+the+diving+board%2C+Casa+Susanna%2C+Hunter%2C+NY_AGO.121772-Standard+Print.jpg)

![Unknown [Sheila and her GG Clarissa and friend, reading Transvestia] 1967 Gelatin silver print 3 5/16 x 4 5/16 in. (8.4 x 10.9 cm) Collection of Betsy Wollheim Photo © AGO](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/52c0509ae4b0330e4569351f/7c014898-8ebf-49bc-8c17-92b403b88b9b/Casa-Susanna-The-Met-Exhibition-LE-MILE-Magazine-Sheila+and+her+GG+Clarissa+and+friend%2C+reading+Transvestia_EXH.169756-Standard+Print.jpg)