.artist talk

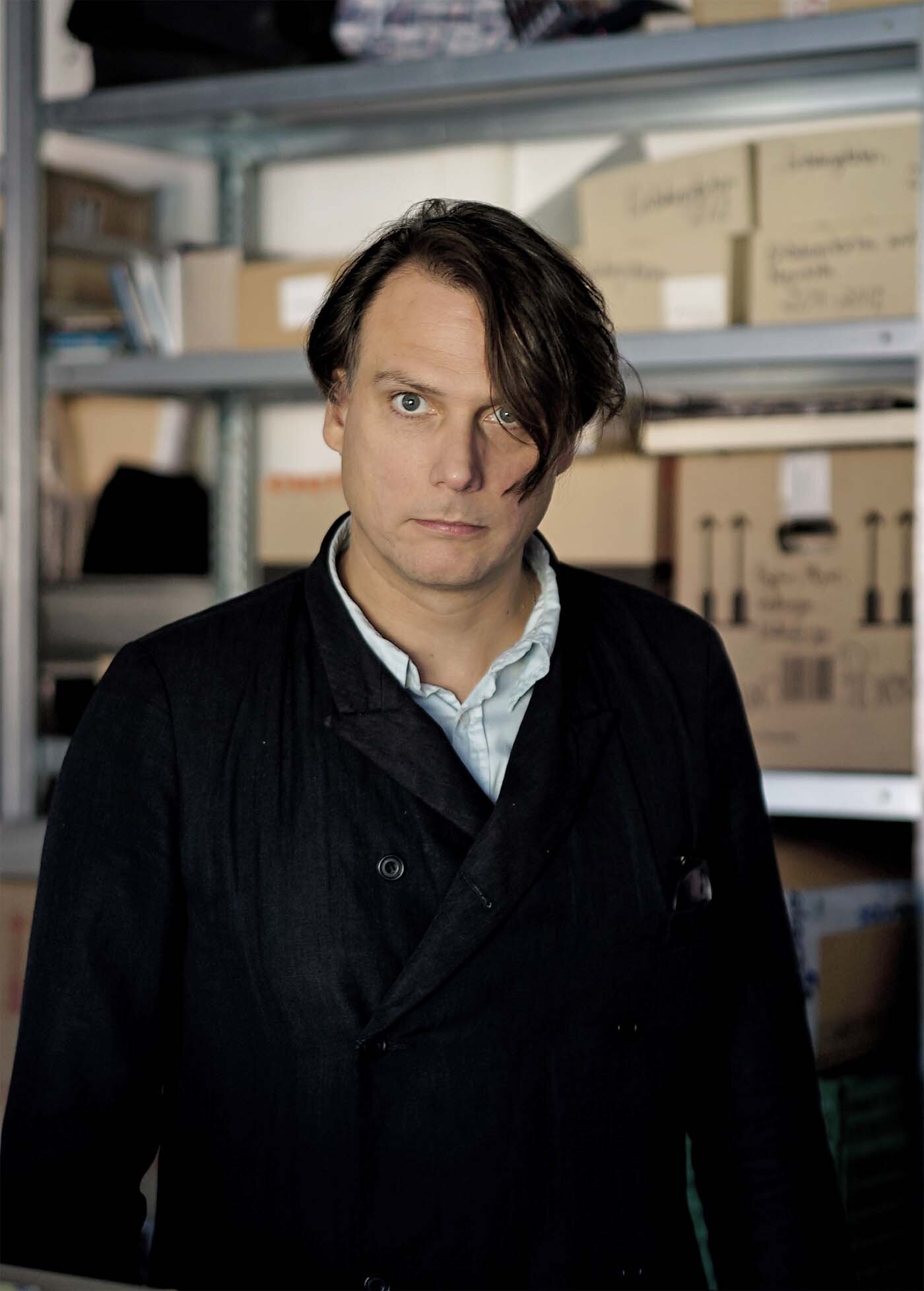

* Gregor Hildebrandt

with Andreas Hübner

There are but few contemporary German-speaking artists who are recognized around the globe for their expertise and dedication to aesthetic excellence. Gregor Hildebrandt, Hesse-born and Berlin-based conceptual virtuoso, is among the chosen few. Since his emergence in the early 2000s, the artist is best known for his signature art practice: cassette tape collages.

Somewhat self-taught in his art, Hildebrandt, a fierce collector of cassette tapes, videotapes, and vinyl records, always follows the very same constructive procedure: He separates magnetic tapes from the audiocassettes, glues the tape bands on canvas, usually vertically, from left to right, and, thus, interweaves songs and paintings.

The songs are well-chosen. Hildebrandt typically shares a strong personal connection with the music he lays out on canvas: The Cure, Björk, Einstürzende Neubauten, Jacques Brel and others have been a part of Hildebrandt’s life for almost four decades. Unsurprisingly then, the titles of his pictures, installations, sculptures, and exhibitions reference song lyrics, poems, and movies. To be sure, the titles, once displayed, develop their own poetical resonance.

Hildebrandt’s approach to art is conceptual. He makes constant use of pre-recorded audio tapes. The linkage between song and canvas builds the composition. In this, the inaudible songs are omnipresent in his paintings, installations, and sculptures. Not unlike an analog storage media archive, his art constitutes a lieu de mémoire, a place of collective and personal memories. His work, in essence, is a mnestic process.

Andreas Hübner sat down with Gregor Hildebrandt to discuss his art, his work ethic, and his obsession with audiocassettes. A fine selection of Gregor Hildebrandt’s sculptures, paintings, and installations is currently on display at G2 Kunsthalle in Leipzig until May 16, 2021.

Gregor, let’s start in medias res. Last year, you were described as a master of audiotape recycling. An apt characterization?

Oh, I was not quite aware, but it seems true in some ways.

Maybe, someone was trying to shed light on the significance of materiality in your work. What’s the origin of your “material” explorations – the long-bygone analog mixtape era? Or are you striving to replace earlier sound archives with aesthetic imaginaries and alternative sound spaces?

I developed my ideas at the end of the 1990s. I looked for ways to transform audio songs. I hoped to integrate a particular song into a sketchbook. The most obvious choice was making use of audiocassettes. At the time, everyone owned cassette recorders which allowed us to record, play and repeat the songs. I recorded a song called “Falschgeld” by Einstürzende Neubauten onto an audiocassette, cut the magnetic tape out of the audiocassette afterwards and stuck it into my sketchbook. More generally speaking, my creative practice is less about recycling or replacing but about adding in a very material sense. The songs I am interested in already exist. They are reproduced and evolve into pictures or installations.

.artist talk

Gregor Hildebrandt

speaks with

Andreas Hübner

first published in:

issue 30, 01/2021

Time and again, exhibition catalogs and press releases emphasize your work ethic. Many enthusiastically emphasize your cutting of audio and VHS tapes into thousands of pieces and fragments. What do you find particularly fascinating about working with magnetic tapes and phonograph records?

The immaterial state of music drives me crazy. You can’t get hold of a song, let alone see it. The idea, or the knowledge, that these magnetic tapes are full of music, or images, is what I find fascinating.

You are mostly employing analog materials. Still, to what extent does your analog practice resonate with the digital world?

If you will, I exploit digital forms of music, for example, when recording a song from Spotify on cassette and mounting the tape onto aluminum panels afterwards. In 2020, I did so in the case of “Schwelle gekreuzt”, a tune which I “embedded” in large wooden baulks that can be read as resonating bodies. However, all this squabbling over analog and digital modes makes me reflect whether digital ways are more practical and convenient. Also, let me draw your attention to an optical reflection of mine in which the printout of a digitally taken photograph is replicated in a mirror made of videotape. I assume you could call such thing an analog reflection of the digital’s own essence.

You often explore different modes of performativity in your art, generating artifacts of inaudible and invisible substance. Is your work political?

I am not quite sure, but I guess my art encapsulates a sort of “political noise.”

credit header imageGregor Hildebrandt

„Schwelle gekreuzt“, 2020

Audio cassette tape, cassette reel, Polyurethane, epoxy resin, aluminium honeycomb panel 74 x 155 x 628 cm (2 parts)

View of the exhibition Fliegen weit vom Ufer fort, Wentrup, Berlin, 2020

Courtesy of the Artist and Wentrup - seen by Roman März