Interview and Film Artist Feature Yuge Zhou

Interview and Film Artist Feature Yuge Zhou

Yuge Zhou

*Reaching for the Other Side

interview & written Mariepet Mangosing

Yuge Zhou got her start as a popular child singer in China, where she starred in many different television shows.

It was during this time as a performer when she quickly learned that she is a born storyteller, though she would later realize that entertainment was not her end-all be-all. She shares, “The experience of performing on stage planted a seed in my heart of wanting to touch people with my own expression.”

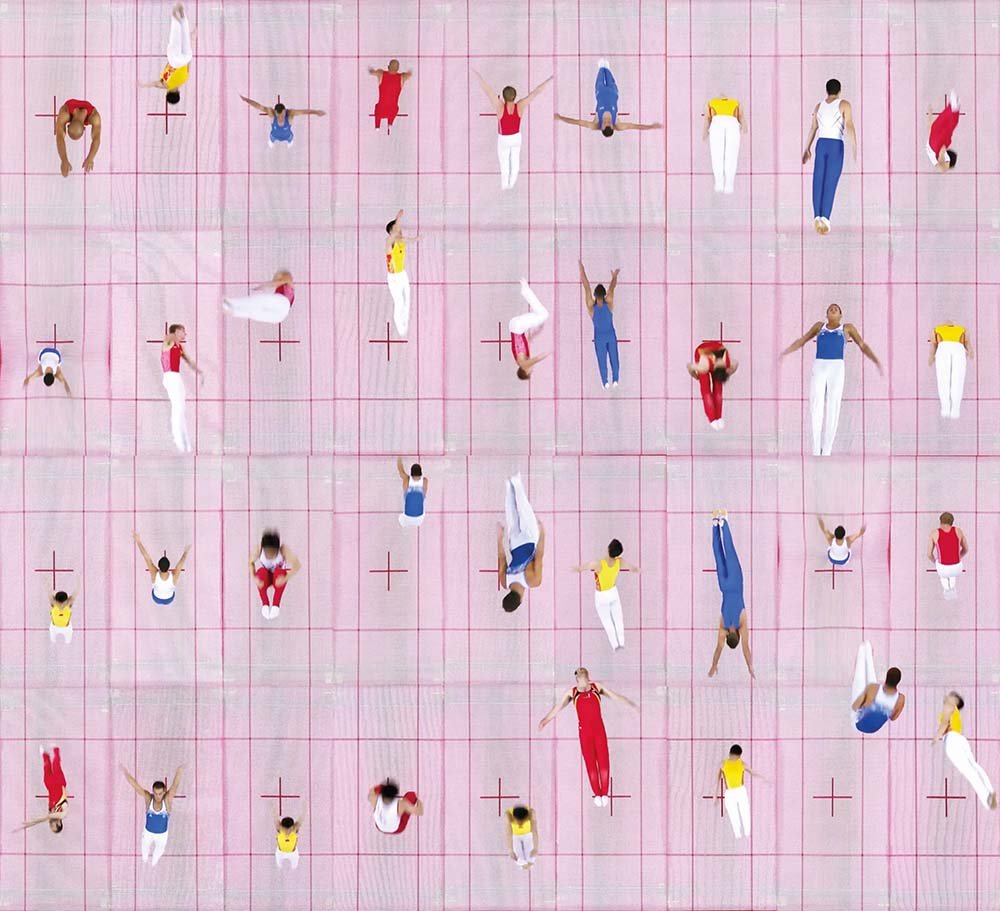

Trampolines Color Exercise

© Yuge Zhou

After leaving China and moving to the United States, Zhou “picked up a camera and started shooting,” which ultimately led her to school. She says, “I went to pursue an MFA at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, where I was able to fuse artistic concepts with the logic associated with technological innovation.”

Not wanting to use conventional structures to tell stories the way films and television do, Zhou began to utilize “non-linear structures that can best be explored through video installations.” Thus, an experimental video artist emerged. She continues, “I find that with video art, I can envelop the viewers with moving images, color, light and sound within a physical or virtual space or place.”

One of Zhou’s main preoccupations is observing humans behaving and gesturing at each other, a subtle communication that is often more powerful than any exchanged words. When approaching her subjects, she explains, “I first notice how people behave as well as their mannerisms, both as individuals and as groups. I’m observing through my own lens so how I read people and my response to them says as much about me as the people I encounter.”

While the distant point-of-view belongs to her, Zhou observes with a sense of intimacy and closeness that directly juxtaposes the vantage point, moving through her work, threading the overall plot and theme scene by scene.

“A lot of the fragmented scenes in my video collages are connected via the flow of gestures. Because there’s no language in my work, gestures are like words that give meaning to the micro-narratives that I ‘stage.’ Ultimately, I’m interested in showing the beauty of human behavior and sometimes its absurdity.”

Pale Patrol (The Humors, part four)

© Yuge Zhou

When the East of the day meets the West of the night (video still)

© Yuge Zhou

When approaching theme, Zhou leans on her bicultural background. “I feel that, at times, I am too Chinese to be American and too American to be Chinese,” she says. “I also find myself longing for home and realizing that both countries are my home. I will always exist in these two cultures as both an outsider and an insider. You can see it from the way I position myself in my work.” Zhou asserts that her identity, centered around this idea of feeling forlorn and desiring roots, is at the helm of anything she does. She comments, “What is interesting after all these years is that I feel like the in-between, this gray area, is actually what is most interesting for me. Now I’m at a place where I’m happy with that. I’m willing to explore this in-between state rather than trying to find one or the other.” In one of her latest series, The Humors, she shoots subjects from an aerial view. She notes,

“The scenes are all filmed from a distance, as I have positioned myself as an observer of the actions, isolated. That has a lot to do with me feeling disconnected from activities but at the same time interested in the connections captured between people.”

Moon Drawings, 2022

© Yuge Zhou

Drawing from her search for a sense of belonging, which is an extension of her dual identity as both Chinese and American, Zhou directs the scene for the viewer to feel that same inherent loneliness, though it seems like there might be an end in sight—marked by the fact that there is another being just on the other side.

In her series, when the East of the day meets the West of the night, Zhou removes people altogether. “The two cameras, like the gaze of protagonists, capture this continuous, slow lateral movement across the horizons as the sun sets and rises from two sides of the Pacific Ocean (China and the United States),” she explains. “Rather than an outsider perspective, this is a first-person point-of-view. That shift has a lot to do with my experience in this country.” While she is still looking out to the horizon, the imagery reads close and intimate because it is directly related to her current physical position. She is still the one on a side but the other beings opposite her are her family and friends in China.

Along with using gestural and behavioral elements to speak to the themes in her work, Zhou finds herself using architecture and landscape as part of the narrative, saying, “Growing up in Beijing, where some of the most modern structures were built around the 2008 Olympic Games, I became more aware of the impact of architecture on a place, as well as the accelerated rhythm of the urban environment.” It’s a curiosity that grounds the viewer with her. She adds, “These transformations led me to see the transience of urban spaces: how familiar places can be suddenly made unfamiliar. I try to capture these ephemeral intersections of lives and stories in my work.”

Her natural curiosity of landscapes and locations led to her award-winning work Project Unity: Ten Miles of Track in One Day. Along with the historical and cultural contexts, the installation draws attention to the Chinese emigrants who built the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Zhou worked with sculptor Hwa-Jeen Na who designed a partially built circle with panels on which Zhou’s video scrolls across miles following the railroad track. Zhou remarks, “I knew right away that I wanted to incorporate a continuous, moving landscape to connect the fragmented pillars. Conceptually, I wanted to do something that would resonate with the Chinese community in America.”

Fueled by the anti-Asian sentiments exacerbated by the pandemic, Zhou recalls, “It didn’t take me long to come upon the history of Chinese transcontinental railroad workers, and I decided to memorialize their identities, thanks to the work of Professor Gordon Chang and his team at the Chinese Railroad Workers in North American Project at Stanford University.” Calling back to the idea that Zhou closely examines people’s behaviors and what that examination conveys about the human condition, Zhou brings to light the workers' names, commemorating them. The project reminds the audience that discrimination against Asian communities is not something novel, rather it has existed all this time and we must finally face that truth.

On the other side of criticism, Zhou’s work meditates on her identity of being a Chinese woman living in America. “My work is meditative,” she says. “It’s rooted in Chinese philosophy, which seeks to find peace beneath the turbulence of daily life. Second, my aesthetics are influenced by traditional scroll paintings, which always illustrate a compressed narrative, multiple events happening at the same time.”

Zhou desires to enjoy the space she takes up between here and there, physically divided by a body of water, a familiar insignia that pops up in her work. “Someone mentioned that they noticed I used water a lot in my work. In when the East of the day meets the West of the night, the water of the Pacific Ocean is a literal, physical barrier between myself and China, my hometown, and my family. At the same time, I know that my family is on the other side. I can’t see them but I know they are out there. The ocean is separating us but also links us together. There is something really powerful and romantic about that, about looking out over the water’s edge in that way.”

Zhou goes on to say that this quality also exists in Love Letters, a project she filmed that features two dancers standing on the east and west banks of the Chicago River, sending messages to one another from afar using gestures. Similarly, Zhou shares, “For the past two winters of the pandemic, while waiting to go back to China to film the second installment (Moon) of when the East of the day meets the West of the night, I filmed myself alone tracing two moon patterns by dragging a suitcase during snowstorms in Chicago, as if to create mantras suspended in a time of waiting.” The use of water does apply here but instead of waves crashing, the water stands frozen, longing to thaw.

In so many ways, Zhou’s work is a playback of her life, a continuous film, curated and installed with the intention of leaving authorial interpretations to the viewer. It is an open-ended approach to interacting with universal themes that speak to the immigrant experience of reaching for community in a different home. It is her direct response to undeserved hatred for her cultural identity. Most notably, the gestalt of Zhou’s work lies within the notion that distance isn’t just a physical barrier. It can be the emotional and mental limitations we hold against each other, as well.

Zhou’s work poses the question: If these limitations were lifted, what would be waiting on the other side for us? Whatever it might be — a sense of community, family, friends, truth, love, home — Zhou’s work insists that it’s worth waiting for and watching it unfold.

credits

(c) Yuge Zhou // The Artist

Artist Talk - Interview with Ania Hobson

#hobson

Artist Talk - Interview with Ania Hobson

#hobson

Ania Hobson

* Strive for Independence

written Abigail Hart

Ania Hobon’s work in portraiture has been awarded some of the most prestigious honors in the art world for a young artist. Her art is intensely appealing and layered with detail and personality. Form, proportion, emotion, fashion choices, and expressive color palettes combine to create narrative portraiture capturing identity and personality.

Based out of Suffolk in the UK, Hobson holds a degree in Fine Art from Ipswich University and has trained at the Royal Drawing School and the Florence Academy of Fine Art.

In 2018, she won the Young Artist award at the BP Portrait Awards hosted by The National Portrait Gallery in London. Her technical skill and fresh take on a very traditional art form like oil on canvas portraiture has made her a rising star in the art world. Hobson speaks candidly about the pressures of the art world and how outside influences can profoundly affect both the artistic output and the personal lives of young artists. Her experience of second-guessing stylistic choices and navigating commercial interests makes the narratives in her art all the more relatable. Hobson has learned to prioritize self-care and in doing so protects her creativity as well as her mental health.

“The art world can be so exciting but the pressure can take a toll on creativity and your emotional well-being, so finding balance is very important.”

Ania Hobson

The idea of balance might be the most prized concept in art and art criticism. Many talented painters strive for balance and each painter expresses it in a unique way. Some find balance on the shimmering edge of a gossamer thread; others find a deep symmetry in color and motion; still others use perfectly defined boundaries to create balance through order and control. The balance in Hobson’s pieces is created by layers and layers of details. Her portraits are both of a single moment in time and also capture an entire lifetime. They show both freedom and restraint, truth to form and geometric exaggeration. Through the layers and dichotomies, what comes through is balance in the form of a person, complete and whole.

Hobson’s use of the word ‘characters’ to refer to the people in her paintings, rather than the traditional ‘subjects,’ is indicative of the importance of narrative in her work. The pieces are not busy with detail, but every element tells a piece of a story. A character’s foot or hand bent out of proportion to face away from another character creates space. A chic black sweater elevates a casual pose to show the character’s backstory. Geometric shapes create motion, restlessness and repose in a composition.

.artist talk

Ania Hobson

speaks with

Abigail Hart

first published in:

issue 30, 01/2021

“I want the viewer to be able to read themselves and their feelings into my paintings and draw their own conclusions of what the politics might be.”

Ania Hobson

Ania Hobson’s portraits tell a complete story with a beginning, middle and end, and every story is unique. Details hint at stories past, present and future and the narratives of her characters become full of life and personality. The beginning could be where the person is now, the middle being where they want to be right now, and the end might be whether they ever get to that place or not. Each story — each portrait — finds the balance of narration and imagination, making the piece infinitely relatable to a viewer.

credit header imageAnia Hobson, 2020

Artist Talk - Interview with Willy Chavarria

Artist Talk - Interview with Willy Chavarria

The Everyman

*Willy Chavarria

written / interview Malcolm Thomas

From prison uniforms to leather bars, Willy Chavarria is designing a future for us all.

“I don’t receive hate mail anymore,” said Willy Chavarria. “I think I shut them all the fuck up,” he wrote on a humid June afternoon. The Mexican-American designer lives part-time with his husband, David, a gemologist, and C-suite executive in Copenhagen. Yet, miles away from Scandinavian domesticity is the fledgling label, that bares Chavarria’s name with an homage to the city that made him a venerable designer-on-the-rise. Willy Chavarria is not yet a household name, but his provocatively inclusive aesthetic has made him a sweet whisper on the sharp tongues of many.

“I first met Willy when he showed at NYFW (New York Fashion Week): Men’s,” wrote CFDA (Council of Fashion Designers of America) President and CEO, Steven Kolb via e-mail. “His show was at the legendary gay bar The Eagle. It was one of the most unique venues. Willy is unique,” he added. The show Kolb is referring to is Willy Chavarria’s controversial Spring/Summer 2018 collection, modeled after the psycho-sexual eighties thriller, Cruising, in which New York City detective, Steven Burns (Al Pacino), goes undercover as a gay S&M enthusiast to catch a sadistic serial killer preying on gay men. It was lauded by the fashion community but ill-received by his own. Fortunately, his audience has “broadened” since then, Chavarria said. And industry kingmakers like Kolb continue to sing the designers praises, “There’s more to clothing in what he does. There’s meaning and message and community.”

A community that begins in casting, “I really like to capture the realness in my work by including the people who inspire me with their own attitude or presence,” said Chavarria of his unorthodox casting methods.

Chavarria uses a Chicano cocktail of models and friends which he uses for shows and campaigns. A method used to categorize the designer by some as more streetwear than luxury. But not surprisingly Chavarria cares as much for labels as he does for bigotry. “Willy works outside the regular fashion circuit. He has created his own circuit of talent that avoids the shallowness we find in so much of the fashion world,” said creative assistant, Zenar Kraige Tobias. “He has mentored me. He has enabled me to believe in myself and be proud of my Brownness.” And Willy can find community just about anywhere. “He cruised me in a nightclub in New Orleans,” said Karlo Steel. Steel is now a consultant and style director for the brand. Growing up in the working-class town of Huron in Fresno County, California, Chavarria did not have such a community. “Since childhood, I have always been an outsider. I grew up in a conservative small town before the internet was invented,” said the designer. “I spent my years being the kid in the cafeteria that ate alone. But I developed a very tough skin and a strong identity.”

An identity that is rooted in self-awareness and social justice reform. Something many industry leaders struggle to understand or implement into their ethos, especially now. “While I do believe that fashion is both a reflection of the world it lives in and a means of inspiration to think, feel and behave differently, I think there is more to having cultural influence than messages in marketing. It is our business infrastructure that must have an impact on society. We can chip away at the system from the top down, or we can change the system from the bottom up,” said Chavarria. And by now, you guessed it, Willy Chavarria always puts his money where his mouth is. From sponsoring undocumented New York City soccer players to creating uniforms for Lurigancho Prison inmates in Peru. “When I created the brand in 2016, my team and I agreed that our brand strategy would be to promote human dignity,” said Chavarria. “The more we grow, the more we are able to give back. I’ve never wanted my work to be entirely exclusive. I truly want all people to feel great in my clothing,” he said.

all looks Willy Chavarria

seen Brent Chua

directed Zenar Kraige

styled Karlo Steel

Hair Takanori Shimura

first published in:

issue 29, 02/2020

And these days? “This year the world pulled the rug from underneath us all. My business was forced to act quickly with big shifts in our business model,” said Chavarria on dealing with the realities of COVID-19. “Normally I am traveling quite a bit between New York and Europe but during the COVID days, everything has been managed remotely. My current collection has been designed and sent to factories without factory visits, but I have been able to work with my team closely via video calls.”

How telling when in January Willy Chavarria unveiled his Fall/Winter 2020 collection to the press. Twenty-pieces in somber variations of black and white. A body of work based on the psychological impacts of global warming. Environmental depression from a world past the point of redemption. At the time, Chavarria emphasized the mortality of time and envisioned a world not so different than the one we are living in now.

But Chavarria is already thinking past our current reality, to the future. “In 2021 I plan to take a slightly more industrial approach to my fashion aesthetic. I think opulence is becoming passé and realness is coming more to the surface of all art and design. I like the idea of people wearing clothing without logos to validate their status. I will introduce a simplicity that combines a tough attitude with compassion. I will be shifting business almost entirely away from a wholesale fashion calendar allowing retailers to buy as needed,” Chavarria said.

“In the midst of chaos, I find peace in creation.” I imagine him pensive at profile, looking out at the world from his window. “It is a way of believing in the future.”

But the right eyes were not always on Chavarria. Like most who operate outside the nepotism of the fashion industry, his journey was a long one. After leaving the conservative mores of Huron behind, Chavarria moved to San Francisco where he earned his Bachelor of Arts in Graphic and Industrial Design in the early ’90s. While attending university, Chavarria picked up a part-time job working in the shipping and packing department at Joe Boxer. Before the end of his college career, he had worked his way into a designer role at the company, designing men’s underwear. In 1999, Chavarria was offered a job at RLX, the athletic leg of Ralph Lauren in New York City. Many moons later, Chavarria launched Palmer Trading Company, in SoHo. A curated emporium of Americana which specialized in artisanal furniture, apparel, and accessories. After nearly a decade of success, Chavarria launched his eponymous menswear line in 2016. In 2018 and ‘19 Willy Chavarria was an International Woolmark Prize finalist, tasked with the challenge of creating environmentally-minded capsule collections made entirely of wool, for an AUD (Australian dollar) $300,000 prize.

Then in 2015, after sixteen years in New York City, Chavarria made a decision. “As the Obama administration came to an end and the next administration revealed itself, we decided this was a good moment,” Chavarria said. “My husband David and I wanted to live in Europe. No sooner did we make the decision; David was offered a job in Copenhagen.” But Chavarria was not turning his back on the city. “We kept our apartment in New York, and I would travel back and forth regularly [pre-COVID19]. David is Puerto Rican from the Boogie Down Bronx, so we are still very much New Yorkers in a strange land, but we enjoy the beauty of a European lifestyle as a healthy change to the chaos of the US. It is still new and inspiring.”

credit header image by Steven Biccard

Unveiling Shadows: Eduardo José Rubio Parra's Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

Unveiling Shadows: Eduardo José Rubio Parra's Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

Unveiling Shadows

*Artistic Rebellion in a Dual World

interview & written Alban E. Smajli

Bridging worlds with a defiant stroke, artist Eduardo José Rubio Parra crashes through cultural barriers in his latest interview with LE MILE Magazine.

A maverick of the art world, Rubio Parra, hailing from Colombia and now a creative force in Antwerp, stitches together the raw, untamed spirit of his homeland with the stark, often enigmatic European sensibilities. His art is not a mere blend; it's a provocative dance across continents, challenging the norms of death, afterlife, and the paranormal.

Gone are the days of art confined to conventional beauty. Rubio Parra's work, steeped in the supernatural, dives headfirst into the abyss of the unknown. In a world where cultures clash and meld, he finds harmony in dissonance, creating a visual language that speaks of both Colombia's vibrant lore and Europe's nuanced mystique. This duality isn't just his canvas; it's his battleground, where he wrestles with the ghosts of two worlds, giving them life through his eclectic artistry.

With The Chopped Off Head Magazine, Rubio Parra cuts deeper than aesthetics. It's a visual scream, a raw expression of frustration and a quest for understanding beyond language barriers. Here, images don't just complement text; they lead the narrative, a testament to Rubio Parra's relentless pursuit to articulate the inarticulable.

.artist talk

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

speaks with

Alban E. Smajli

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL II, 2023

wearing Martine Rose

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL I, 2023

wearing Loewe

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

ANGEL III, 2023

wearing Vivienne Westwood

Graphite and colored pencils on paper

88,5 x 68 cm

Alban E. Smajli

Your art intricately ties your Colombian heritage with the European influences you've been surrounded by. How do you navigate this duality, especially when it comes to exploring topics of death, afterlife, and the unknown?

Eduardo José Rubio Parra

It may sound naive, and I probably was, but when moving from Colombia to Germany in 2015, I was not aware of how different cultures really are. It's not only language and customs, but also how we perceive ourselves, our surroundings, and especially that what is unknown to us. Growing up in Colombia, and I would dare say Latin America, stories of the supernatural are pervalent in society. It's not necessary to believe in it to know a person or people who have seen, felt, and or heard something that cannot be explained by the laws of nature.

I've always been fascinated by these stories, and during my time as an art student, I felt the urge to use them as references in the process of making art. But in this process, I soon realized that in Germany the perception of the supernatural is completely different from Colombia and Latin America. This made people not as engaged with my work as I wanted them to be, because it was too far from what they know. So I began to look for a way to "blur" the difference. I wanted my work to serve as a bridge between the world I grew up in -Colombia- and the one I was getting to know -Germany-. I realized that we can all relate to something that is strange or mysterious, especially in a creepy way. So the cornerstone of the bridge turned out to be "uncanniness".

The title of your publication, "The Chopped Off Head Magazine", is evocative and deeply personal. Could you elaborate on the moment or instance when this concept took root? How does the process of "chopping off one's head" to expose internal realities shape the content and presentation of your magazine?

The title of the magazine reflects what I felt every time I talked about my work without being able to make myself understood. Especially in a foreign language. When I had clear images in my head of what I was talking about, but found it difficult to translate them into words. At those times I wished I could cut my head off to show people those images. For this reason, "The Chopped Off Head Magazine" is predominantly visual. The first issue focused on me and my artistic practice, but from the second issue on, I will invite other artists and designers to "chop their heads off". The content and form of the future issues will be significantly influenced by the artists and designers and their interpretation of the concept of the magazine.

You've explored the realm of drawing and its inherent authenticity extensively. How has this exploration evolved over time, and in what ways has it informed your approach to other mediums, such as special effects makeup or performance art?

In fact, it was the other way around. The creation of characters based on me has always been an important aspect of my work. Through these characters, I study, among others, identity, supernatural phenomena, and fashion. Initially, I created characters for photo and video performances, making use of costumes and my skills as a special effects makeup artist.

Lately, I create these characters making use of the medium of Drawing as well. The medium of Drawing creates a distance between me and the characters, allowing them to exist more independently. With a photo and/or video, the characters' existence depends on me disguising myself for the camera. When I see a photo and/or video of these characters, I know I'm seeing myself. With a drawing, I can't assure that. The moment I come to this realization, the characters get to have a life of their own and everything seems possible within a drawing.

With a keen interest in blurring the lines between reality and fiction, how do you see fashion's role in challenging societal norms or perceptions? In what ways does your work in fashion editorials push the envelope in terms of content and presentation?

Fashion has always been a reference in my work. I love watching fashion shows and I'm fascinated by the great variety of characters that are created for a single catwalk. Characters that I only see for a couple of seconds, but their image is so striking that it sticks in my head for a long time. I like to create stories for these characters and imagine who they would be in the real world. I'm especially fascinated by how the same model can embody different characters. This fascination led me to start my latest and probably biggest project. "ANGEL" is an ongoing series of drawings consisting of portraits of different versions of myself. Each version embodies a vision of who I would like to be.

As humans, we have all experienced the desire to be someone else, but letting insecurities or life circumstances hold us back. My drawings allow me to be different versions of myself, unexposed, and be unapologetic about it. Starting from a place of doubt, fear, and limitations, my aim is to create characters and drawings that manifest the opposite and rather "exude" power. For each drawing, my identity is transformed through the use of existing fashion garments and different hairstyles. I see fashion as an enabler for personality change. Despite this work being very personal, identity, vulnerability, and empowerment concern us all.

You mentioned a desire to collaborate with other artists for future editions of "The Chopped Off Head Magazine". What qualities or perspectives are you seeking in these artists, and how do you envision these collaborations amplifying the magazine's ethos and message?

"The Chopped off Head Magazine" is all about collaboration! The magazine is meant to serve as a bridge between different artists, artistic disciplines, and cultures. The idea is to create an ever growing interdisciplinary and intercultural network and an international platform for the presentation of contemporary art, fashion and visual culture. The second issue, called "The Chopped Off Head Magazine: The Dead or Alive Issue", will be co-created by German artist Hannes Dünnebier and will deal with the topics death, life after death, supernatural phenomena, and the unknown. Death, for example, is a topic that concerns us all – however, due to the different contexts in which we grow and develop as individuals, our understanding of this concept is not the same. I am particularly interested in these differences and want to use them as the starting point for creation. The broader the perspectives, the better.

credits

(c) Eduardo José Rubio Parra - all images seen by Marvis Chan

Artist Talk - Interview with Red Rubber Road

Artist Talk - Interview with Red Rubber Road

.aesthetic talk

* Red Rubber Road

written & interview Philipp Schreiner

edited Hannah Rose Prendergast

Red Rubber Road is the ongoing photographic journey of Spanish artist AnaHell and Swiss/ Spanish artist Nathalie Dreier. Their work has been shown at exhibitions throughout Europe and published in various magazines. Since 2015, the duo has reflected on intimacy and personal boundaries within relationships using their bodies as sculptural entities.

„We don’t define anyone as our hero, but we believe everyone can be heroic,”

Red Rubber Road develops fluid hybrid forms in which the beauty of human nudity merges into formless states of being. In their playful arrangements, the two photographers move in the artistic field of tension between staged and scenic photography characterized by performative play.

For example, the staged process behind the series „Raum in Raum“ differs from their focus in “Together A Part” in its detailed, elaborate preparation for one scenic shot they had in mind. On the other hand, staged photography leaves more space for coincidences and spontaneous adaptation.

The viewer experiences the artwork’s aestheticism as their eyes scan the body landscapes, gazing from rock-like elevations to the valley between two shoulder blades, balanced elsewhere by the curvature of collarbones. On the border between two-dimensional photographs and three- dimensional sculptural illusions, the dividing lines between pictorial space and viewer space, between seeing and feeling, become blurred.

The creation of these intimate photographs requires familiarity and a close connection. Whatever challenges or pleasant circumstances the work brings with it and what their creative inspiration benefits from are shared here so that all of us can take a walk down Red Rubber Road.

Philipp Schreiner //

WHAT BROUGHT YOU TOGETHER AS COLLABORATORS PERSONALLY AND ARTISTICALLY?

Red Rubber Road //

We’ve known each other since we were pre-teens, and we have such a strong connection and understanding of each other that we are really in sync when shooting, and we can communicate non-verbally if necessary. When you are completely comfortable with someone, and you can feed off of each other’s creative ideas, it makes it really beautiful to work together. We both enjoy self-portraiture because we only need to depend on ourselves/each other, and it gives us a lot of freedom to create what we want. It’s also amazing to work as a duo because you can voice your ideas and bounce them back and forth until they materialize.

WHAT FASCINATES YOU ABOUT THE HUMAN BODY?

The human body is one of the most accessible tools for self-expression. In our images, we can use our bodies in ways that transcend our individual identity, transform- ing ourselves to create momentary sculptures, otherworldly creatures, or tell stories.

Through our bodies, we can use all of our senses to interact and connect with the world around us. Simultaneously, the body is also undergoing constant change, which makes it fascinating to work with long-term because, in a sense, it also becomes a document of our lives. For us, nudity is a very natural state of being without the distraction of clothing that often indicates a style or a time period too clearly. In order to better merge our identities, we like to use nudity almost like a uniform.

WHAT IS THE BIGGEST CHALLENGE IN DEVELOPING IDEAS AS AN ARTIST COLLECTIVE?

The biggest challenge isn’t coming up with ideas, although sometimes executing them can be quite challenging. Much of our work has a very spontaneous process, so we’re constantly developing and sharing ideas on the go; It’s very fluid and easy.

.artist talk

AnaHell & Nathalie Dreier

speaks with

Philipp Schreiner

first published in Issue Nr. 32, 01/2022

THE GO; IT’S VERY FLUID AND EASY. WHAT INSPIRED YOU TO CREATE THE SERIES “TOGETHER A PART” DURING THE FIRST LOCKDOWN IN 2020?

When COVID started, we were supposed to be shooting together in rural Spain. Instead, we both found ourselves in quarantine in different countries, and we started exploring new collaborative options. Our communication was through digital devices, so naturally, we gravitated towards including them in our work.

In Together A Part, we took turns shooting from our respective ho- mes, interacting and merging solely through a screen. Eventually, we started investigating how digital devices affect relationships, not only in times of social distancing.

DID ANA’S MONTH-LONG 2018 HOSPITAL STAY IN ISOLATION FOR AN INFECTIOUS DISEASE HELP PREPARE YOU FOR SOCIAL DISTANCING MEASURES AND DIGITAL COMMUNICATION?

The funny story is that AnaHell didn’t have WiFi at the hospital, so it didn’t even occur to us to work together online. What we shot there together was during Nathalie’s visits to the hospital.

The situation was also very different since AnaHell had limitations due to her health condition that we didn’t have during the 2020 lockdown. Shooting together was definitely a great coping mechanism, though, since it helps to have an artistic outlet when going through hard times.

DO YOU THINK TOUGH SITUATIONS CATALYZE IDEAS AND THE WORKING PROCESS, OR DOES INSPIRATION ALSO HIT WHEN EVERYTHING IS FINE IN YOUR PERSONAL LIFE?

We both believe in the creative power of limitations, and some- times certain circumstances can be an extra boost of inspiration. We certainly don’t think that we need to be in tough personal situations to feel more creative – our motto is to work with what we have, whatever that may be.

HOW IMPORTANT ARE POLITICS, SOCIETY, AND WORLDWIDE AFFAIRS TO YOUR WORK?

Indirectly, society and the state of the world always affect our view on things and the circumstances in which we create. Covid definitely showed us that. However, we perceive our work as something inherently personal.

WHO DO YOU CONSIDER TO BE A HERO?

We don’t define anyone as our hero, but we believe everyone can be heroic.

WHAT NEW PROJECTS HAVE YOU BEEN WORKING ON?

We’ve been diving into the world of screens and are exploring new ways of playing with technology.

credit all images

(c) the artists RED RUBBER ROAD

Artistic Anarchy with Hannes Dünnebier

Artistic Anarchy with Hannes Dünnebier

Rebel Threads

*Hannes Dünnebier's Artistic Anarchy

interview & written Alban E. Smajli

Hannes Dünnebier is redrawing the lines of reality. In his world, graphite whispers and cotton screams, creating a narrative that's less about creating and more about upending.

His journey? A plunge from the realms of large-scale drawings into the tactile embrace of textile. This isn't just a shift in medium; it's a manifesto, a defiant stride into the uncharted.

Hannes Dünnebier

Untitled, 2023

hand-stitched & hand-painted heeled boots, acrylic paint & varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

.artist talk

Hannes Dünnebier

speaks with

Alban E. Smajli

As he navigates the intricate interplay of pencil and fabric, Dünnebier is stitching a new world order, thread by thread, line by line. With every piece, he questions, he defies, he redefines. His work is a mirror, a window, inviting us to step through and lose ourselves in a universe where the familiar is strange, and the strange, intimately familiar.

Hannes Dünnebier

Untitled, 2023

six pairs of hand-stitched & hand-painted, shoes, acrylic paint & varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

Alban E. Smajli //

You've brilliantly used the medium of drawing to explore the challenges of human existence and its relationship with social norms, faith, and superstitions. How do you see the evolution of your artistic journey from large-scale graphite drawings to your recent textile works? And how do these two mediums connect and converse with each other in your practice?

Hannes Dünnebier //

Besides pencil and paper, I was always attracted to raw cotton fabric, that’s commonly used as the base for classic oil and acrylic painting. I looked for ways to incorporate it into my drawing practice, for example by sewing a fictitious drawing garment in which the graphite pencils are lined up in a cartridge belt.

Last year I moved to Antwerp to do a Masters at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, which was a good place to further deepen my exploration of the raw cotton fabric and its interconnection with my drawing practice. One thing that has always particularly inspired me about drawing is that I can create complex works and an entire world with the simplest of means. I wanted to try to do the same with the fabric, which I first manipulated, to achieve different looks and feels and then hand-stitched into clothing and shoe-like objects.

I started by recreating a few pieces from my personal wardrobe, such as a sports jacket or trainers, and then added new, self-invented pieces such as high heels with a hand-painted crocodile skin pattern. I also made a shoulder bag, inspired by a random bag I found in a second-hand shop in Antwerp. For the graduation show I staged everything together in a room as a kind of extended self-portrait.

For me it’s a continuation of my drawing practice and I see the textile works as drawings themselves. The process of hand sewing plays an important role in this. Sewing a piece together stitch by stitch is similar to how I put my drawings together line by line. I guess that in the end my graphite drawings and my textile works all come from the same vague feeling – it just appears in different forms.

Congratulations on being awarded the Lyonel Kunstpreis. The jury mentioned your art offers "an immense interest in the familiar in the seemingly new." How do you interpret this? And how does the cyclical nature of old appearing in new forms manifest in your work?

Thank you! I think when creating an artwork, it’s a lot about the fusion of different existing things, into something new. References can be obvious, and used as a sort of quote, but sometimes it’s nice to keep it subtle and try to create a sense of familiarity that cannot be deciphered immediately. The balance between the known and the unknown, between the readable and the unreadable is something I encounter a lot when making art. It's about trying to carve out vagueness as clearly as possible - if that makes any sense.

The jury also highlighted the role of the human body in your work, both as a site of manipulation and a medium for self-expression. Can you elaborate on how you navigate this dichotomy and what inspired you to approach the body in such a unique manner?

This makes me think of one of my first projects in art school, where I designed furniture for specific body positions, that were all based on having really bad posture. My idea was to use the posture as a metaphor for the mental state of a person and manifest that in an entire interior setting. I always found it weird to have a body, that physically exists in space, and I am trying to make sense out of it by using its presence and its absence as means for my art. The first approach with the furniture has evolved with time but the core idea is still inherent in my work today.

In my graduation show at the Royal Academy, for example, all pieces originally scaled to a body (my body) were shown abandoned and inanimate, evoking a feeling of absence and emptiness. They were still tracing bodily presence and interaction, but also raised questions about their potential autonomous existence.

Hannes Dünnebier

Sorry not Sorry, 2023

hand-stitched and hand-painted shoulder bag, acrylic paint and varnish on raw cotton fabric, dimensions variable

In the "Intrawelten" exhibition, you showcased various intriguing pieces from your diploma exhibition "BYE!", including the graphite drawing with the Nelly Furtado lyric quote and other items such as the Styrodur shoes. Could you elaborate on the central theme connecting these artworks and your choice of objects, especially the quote from Nelly Furtado?

In my exhibition “BYE!” I combined different types of works, such as drawings, textile works and styrofoam shoes to create a stage-like setting. The central theme of the exhibition was an imaginary performance, for which I chose “All Good Things” by Nelly Furtado as the underlying soundtrack. I reawakened my love for this song, while I went through a phase of listening to 2000s pop songs as a sort of therapeutic time travel at the time of making the exhibition.

It’s a gloomy and melancholic song but at the same time it’s very hooky – which is a duality that I resonate with a lot. For the exhibition I took out the central line “Why do all good things come to an end?” and placed it as the only colour element onto a large-scale graphite drawing. I like to think about it as a timeless and universal question. Maybe one of the central questions of human existence. It’s a bit deep but not that deep after all.

With your recognition and the support from institutions, what future projects or explorations are you most excited about? And how do you envision the next phase of your artistic journey?

It’s a very busy time ahead, which I am looking forward to. Together with Colombian artist Eduardo José Rubio Parra, I will co-create the second issue of the experimental publication project THE CHOPPED OFF HEAD MAGAZINE featuring new textile works of mine, and I plan on hosting a series of events in my studio here in Antwerp. I also started a new series of drawings, and besides began to collaborate with young fashion designers on my further exploration of textile and garment, which turns out to be a very fruitful conversation.

(c) Hannes Dünnebier - all images seen by Marvis Chan

Artist Talk - Interview with George Byrne

Artist Talk - Interview with George Byrne

.aesthetic talk

*George Byrne

written Jessah Amarante

Minimalism can be described as the grandchild of the Bauhaus movement and is a stripped down version of a bigger image, thought, or idea.

Minimalist art and design offer us a pure and simple form of beauty that can represent truth, order, simplicity, and harmony (because it doesn’t pretend to be what it isn’t). Musician-Minimal Photographer George Byrne, Brother of Actress Rose Byrne, based in the city of Los Angeles, the photographer aims to use natural lighting, contrast, and shadows to depict his minimalistic approach of abstract direction. Developed in the USA in the 1960s and typified by artworks composed of simple geometric shapes based on the square and the rectangle, Byrne has mastered capturing the essence of LA solitude and calmness in a still of disposable architectures, landscapes of bright colors in symmetry. Born in Sydney in 1976, graduated from College Of The Arts in 2001, traveled globally for exploration to see where he wanted to settle down until he landed permanently in Los Angeles in 2010 where he has been focusing on his photographic practices ever since.

.artist talk

George Byrne

speaks with

Jessah Amarante

first published in:

Issue Nr. 25, 02/2018

Minimalism is a term referring to those movements or styles in various forms of art and design, especially visual art and music, where the work of art is reduced to its necessary elements. In Byrne’s work, you’ll get to see that he allows these images to come across as simple, clean, and timeless.

WHAT ARE YOU WORKING ON RIGHT NOW?

Right now, I’m preparing work for a solo exhibition in Oslo, Norway

YOU HAVE MENTIONED “COLOR, CONTOUR & TEXTURE” FOR THE “NEW ORDER” SERIES. IS THAT THE MEDIUM YOU USE FOR ALL OF YOUR PHOTOGRAPHY WORK?

Yes, to a degree, but for the New Order series I chose to move away from more traditional, literal landscapes and push the work closer to pure abstraction.

PEOPLE ADVOCATE YOUR WORK TO BE THE ‘MODERNIST PAINTINGS”, CAPTURING THE SUBLIMINAL IN THE SUBLIME. WHAT ARE THE STAKES OF ‘MODERNIST PAINTINGS’ AND DO YOU AGREE THAT YOUR CRAFT HAS PAINTERLY ABSTRACT IMPRESSIONS?

I suppose the stakes of Modernist painting would be the challenge of creating something complex and interesting without doing too much. To explore a sort of refined efficiency in mark making and expression & to look at the base relationship of color and form and composition. It’s quite childlike in a way but it’s actually very hard to do well. I was painting before I was taking photographs and - as a painter - I was very much taking cues from Modernist masters, so I think those instincts are alive and well in these photographs. The cool thing about this series is that, because I was I’m now working in a different medium (photography not paint), these painterly influences came about more intuitively, almost by accident.

HAVE YOU EVER COME ACROSS CREATIVE BLOCKS AND IF YES, HOW DO YOU OVERCOME THEM?

I tend to have the opposite problem, I take way too many pictures and have too many ideas stumbling over each other in my head. What I’ve learned in the few years that I’ve been a full-time artist is that the exhibition process is crucial to the discipline of creating coherent bodies of work. It’s very similar to the experience I’ve had being a musician in that every year or two you release an LP with 12 songs, and each LP takes the DNA form the previous release and builds on it, and things evolve.

Hyperion 2015

© Courtesy George Byrne

Burbank

© Courtesy George Byrne

YOU HAVE COMPOSED NUMEROUS MUSIC ALBUMS OVER THE LAST COUPLE YEARS. IS THERE ONE IN PARTICULAR THAT RESONATES WITH YOU THE MOST?

I have a new song I released called Stars & Stripes so I’d say that is the one resonating most at present.

LOS FELIZ, LOS ANGELES HAS BEEN THE FOCAL POINT OF YOUR CANVAS SINCE 2010. WHAT OTHER CITY/COUNTRY HAVE YOU SET YOUR EYES ON NEXT? IS THERE ANY?

Yes, I would love to spend some time in Las Vegas, Miami and the state of Texas.

WHAT IMPRESSION WOULD YOU LIKE PEOPLE TO HAVE WHEN SEEING YOUR WORKS?

I think the feeling you get when you’re moved by a piece of art of music is a cellular one, it’s not intellectual, you feel it in your chest and mind. It’s quite magic. Like when a song has always moved you to tears but you’ve never understood a single lyric (*thanks Bon Iver). I’d just love for my art to make people feel alive & inspired. All that good stuff.

IF YOUR PHOTOGRAPHY WORK COULD TALK, WHAT WOULD IT SAY?

That’s a good Q! Being from LA, they would probably engage you in a scintillating chat about how good the weather is & how their audition went the previous day...other than that perhaps what my work is communicating is that there is magic, mystery and beauty everywhere, you just have to keep your eyes open.

credit header image

© Courtesy George Byrne

Artist Talk - Interview with Pelle Cass

Artist Talk - Interview with Pelle Cass

.aesthetic talk

People Watching with *Pelle Cass

with Hannah Rose Prendergast

For Pelle Cass, people-watching is a necessary part of his job. The Massachusetts-based street photographer debuted his series “Selected People” over a decade ago, and it has continued to inform the human experience ever since.

In 2020, Cass began to reconstruct his images to account for the new normal — “Selected People” became socially distanced and what started as “Crowded Fields” in 2017 dissipated to show non-contact sports. In any case, Cass abides by his cardinal rule of photography: “everything remains in its exact original place, and nothing is changed, only kept or dropped.” Time-lapsed into a single frame, the result looks unbelievable, but rest assured, it all happened in a day’s work.

Pelle Cass

High Line (colors), 2013

(c) Pelle Cass

.artist talk

Pelle Cass

speaks with

Hannah Rose Prendergast

first published in issue 30, 01/2021

SINCE THE PANDEMIC, YOU’VE HAD TO REWORK YOUR ARCHIVES TO REFLECT SOCIAL DISTANCING. WHAT HAS BEEN THE MOST CHALLENGING PART OF REIMAGINING YOUR WORK? WILL IT EVER LOOK THE SAME?

In early March, I’d planned to do two commissions in Europe and one in the US. It all came to a halt in the middle of March when Massachusetts shut down. The whole thing was awful and disorienting; it was frightening just to walk around the neighborhood. Everything looked strange and sad, multiplied by the knowledge that everybody else in the world was suffering. It’s uncomfortable to admit, but the nervous energy and fear of those days, dire as they felt, had the same effect on me as excitement. I was in a kind of creative panic; it was surprisingly easy to get to work.

In April, the idea of social distance was completely novel to me but devastatingly real. It made my pictures look wrong — crowded, filled with activity, and utterly irrelevant. The current mood was silent, attenuated, and somber. My photos looked like relics. I realized I could rework them to be empty, to look like what was unfolding in the real world that I was prohibited from entering. It should be hard to focus on the trivial work of art-making when your heart is breaking, but it wasn’t. I was very lucky to have no particular personal hardship during the lockdown, but I was tense, afraid, and aware that most people were worse off than me.

I don’t know how this period will affect my work. I haven’t been out in public beyond my neighborhood, so I haven’t taken any new pictures of people on the street. Of course, photographing sports is out of the question for now, but I’d like to keep trying new things — fashion, dance, and other bodies in motion. The pandemic will pass one day, and I hope to remain open to new things and new ideas.

YOUR “STRANGER” PORTRAIT SERIES DEMONSTRATES THAT THE WHOLE IS GREATER THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS. ARE “SELECTED PEOPLE” AND “CROWDED FIELDS” SIMILAR IN THIS RESPECT?

In my “Strangers” series, I tried to devise a new kind of portrait, one that says nothing about personality or resemblance. The paradox is that these portraits are made up of many extremely accurate observations that don’t add up to what we think of when we think of portraiture. The pictures look nothing like the people they depict!

“Selected People” and “Crowded Fields” take a different tack. They let time pile up so that the photos convey much more information than an ordinary still photo. Further, the process allows me to add a subjective angle. I don’t want to simply compile all the events of a given hour. I select events that interest me and skip the ones that don’t. The viewer gets more than a record of a game or a street corner; the pictures convey my thoughts and feelings.

ONE OF YOUR RULES IS THAT IF TWINS WANDER INTO THE FRAME, YOU LEAVE THEM IN SO THAT PEOPLE THINK IT’S A PHOTOSHOP TRICK. HOW OFTEN DOES THIS HAPPEN?

It’s very rare for twins to turn up, unfortunately. But I use the principal all of the time, which is to include a lot of true stuff, so the trickier bits look more real.

For example, athletes in uniform all look the same, so I can include natural clusters of figures along with photoshopped ones, and it’s hard to tell one from the other. Animals tend to look the same as our species, so including multiples of an individual can easily fool the eye into thinking it’s many individuals. It works for dogs and birds, but footballs, tennis balls, and hockey pucks, too.

RECENTLY YOU WERE COMMISSIONED TO DO A FASHION SHOOT FOR SSENSE. WHAT WAS THIS EXPERIENCE LIKE FOR YOU COMPARED TO A TYPICAL SHOOT?

SSENSE shipped me a big box of clothing. I tossed each item up in the air and photographed it. Then, just like “Selected People” or “Crowded Fields,” I combined the elements in Photoshop, keeping each item of clothing in its real, original place in the sky. The biggest difference was that I could control my subjects, although the wind kept things unpredictable. It was also quite strenuous to toss the clothing thousands of times as high as I could. Meanwhile, I had to learn to press the cable release with my other hand at just the right instant. It was summer, and it was hot! I enjoyed moving around since usually, I’m rooted in one spot for the length of a lacrosse game or swim meet. It was also nice to have coworkers — the good people at SSENSE who offered support and made the pictures better with their insights and suggestions. I normally work alone, so this was more collaborative than usual. It was also entirely new for me, even though it relied on some tricks I’d developed before.

YOU’VE SAID BEFORE THAT YOUR INSISTENCE ON THE TRUTH HAS NOTHING TO DO WITH ART AND EVERYTHING TO DO WITH JOURNALISTIC INTEGRITY. WHY IS THIS DISTINICTION SO IMPORTANT TO YOU?

My photography education revolved mostly around documentary and street photography and ideals of truth and accuracy. It started as a received idea, one that I’ve rejected at times since. Photographs can lie, too. That’s the whole point of The Pictures Generation from Cindy Sherman on down. But even the most out-of-context, lying photograph conveys so much more factual information about the world than painting, for example. Photography’s fact-gathering is a miracle that stuns me every day. You can point a camera at the most complicated thing in the world, or the planet itself, and the camera will record it all, every bit. So maybe I’m more connected to journalism than I think! My pictures may look false — they are not what the eye sees in a single instant — but they are more true to how we remember an hour of time, a crowded mish-mosh of images, and important moments elbowing to the front.

IN A WAY, YOUR WORK RENDERS COMPETITION MEANINGLESS.

DO YOU THINK SEEING THIS BRINGS PEOPLE CLOSER TOGETHER?

I think my photos try to scramble sports so that you can’t tell who’s winning or losing or even what the players are trying to accomplish on the field. The players are no longer enemies or contestants. They appear to be cooperating, arraying themselves according to some kind of principle of aesthetic pleasure or oddity. And, literally speaking, my photos do bring people closer together. Ideally, after you looked at one of my pictures, you would turn off your computer, go outside, and find a bunch of people to play with.

Pelle Cass

Mass Ave Bridge, 2020

(c) Pelle Cass